The Network is Intelligence: How Urbanization, Connectivity, and Clusters Shaped Human Advancement

From Cities to Supercomputers: Why Intelligence Depends on Connection

In the early 1980s, Sun Microsystems—a leading disruptor in Silicon Valley—coined the phrase: “The Network is the Computer.” At the time, it was a bold claim. Networking infrastructure was still limited, and standalone machines dominated the computing landscape. Yet today, the idea is self-evident: without connectivity, a smartphone or PC is little more than a calculator. The true power of modern devices lies in their ability to access, exchange, and process data via networks.

In supercomputing, the same principle holds. Modern supercomputers, like the U.S.’s El Capitan, achieve their power not just through raw processor speed, but by linking up over 11,000 nodes, each of which is a computing unit with CPU and memory, via ultra-fast connectivity function called interconnect. The speed and flexibility of these interconnections define a supercomputer’s capabilities far more than individual node performance.

A powerful processor is useless without timely access to the right data. Connectivity—whether the internet or interconnect—is what enables meaningful computation. In this sense, Sun Microsystems was prophetic: the network is the computer.

The Human Brain as a Node

We can extend this analogy to human intelligence. A brain is like a computing node—capable of memory and processing. But even a highly capable brain, if isolated, cannot achieve its full potential. This is evident in cases of extreme social deprivation, where individuals raised without human interaction often suffer severe cognitive impairment.

Modern societies understand this intuitively. We load human brains—especially those of children—with knowledge from family, schools, books, media, and the internet. The more diverse and structured the input, the more sophisticated the output. Intelligence is not simply a product of raw brainpower; it is shaped by access to the right information.

The Pre-Modern World: Where Was the Network?

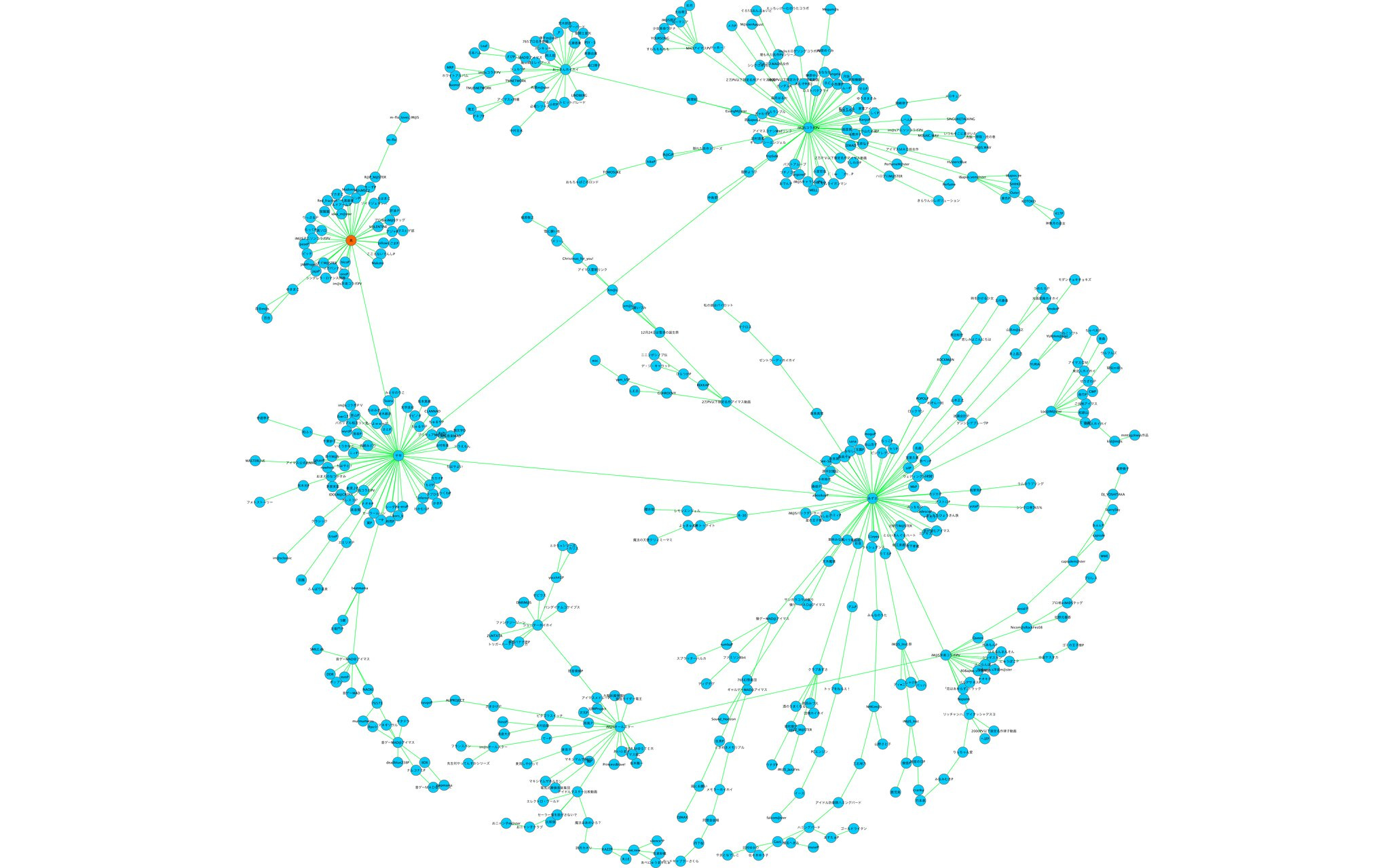

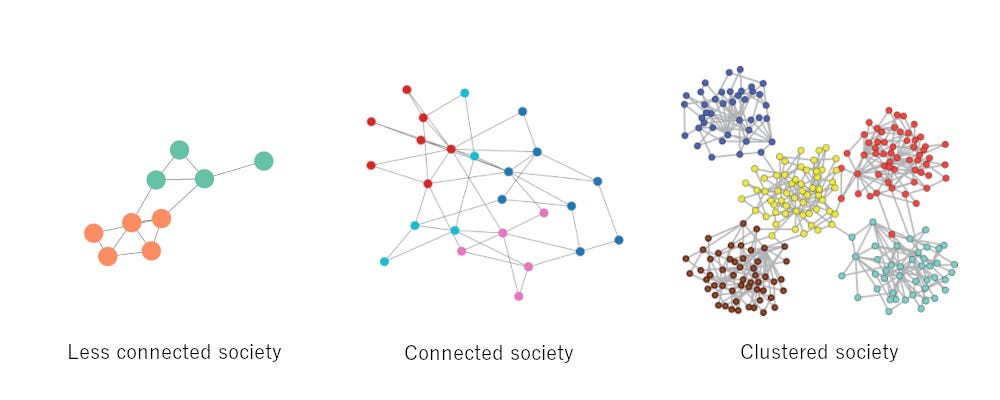

In pre-modern societies, before mass media and formal schooling were widespread, the primary source of information was direct human interaction. This raises two key questions: Which regions provided environments rich in social and informational exchange? And why did some societies industrialize and modernize faster than others?

The answer lies in foundational factors: urbanization and transportation efficiency.

Densely populated cities, especially those connected by water-based transport (rivers, seas, canals), enabled frequent and varied exchanges of information. Unlike land transport, water transport was far more efficient and scalable, making cities accessible and commercially vibrant. These urban hubs became information hubs—places where people and ideas converged.

Specialization and Clusters

As societies matured, they began forming specialized communities—clusters of people working in similar trades or intellectual domains. This allowed knowledge to accumulate and circulate within defined networks. The blacksmith learned from the guild master; the physician studied ancient and contemporary texts; the astronomer joined a society of peers.

This clustering of intellectual and professional activity led to exponential knowledge growth in certain regions. The Renaissance in Florence or the Royal Society of London are classic examples: environments where dense, specialized communication catalyzed innovation and discovery. The network, in essence, became the intelligence.

Two Key Drivers of Clustering

Two forces fueled the creation of these clusters:

Organizations

Urban, commercially vibrant areas gave rise to organizations—workshops, guilds, trading firms, academic societies. These groups provided structure and continuity for knowledge-sharing across generations. Within an organization, skills were passed down, refined, and disseminated across networks of practitioners.Printed media

Following Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press, Europe saw an explosion in written knowledge. Though printed media was not household items at first, books and pamphlets circulated among professionals, merchants, scholars, clergy, and students—predominantly urban dwellers. Universities and academies collected books and scholars alike, creating deep, connected reservoirs of information—similar to how the internet functions today.

The Root of the Great Divergence

The “Great Divergence” between industrializing and non-industrializing societies was not a matter of IQ or innate capability. It was driven by structural conditions. Societies with dense urbanization, efficient transport, (especially via water. For more information about the effect of water transportation, click here) and vibrant commercial and intellectual institutions formed the kinds of networks that enabled rapid progress.

These societies became fertile ground for clusters—groups of specialists exchanging and refining knowledge in everything from metallurgy and medicine to navigation and mathematics. The network—not the individual—was the engine of advancement.

The network is not just the computer. The network is the intelligence.

Very good piece.

Remember, humans aren’t much more intelligent than our pre-human ancestors.

What made homo-sapiens special was our ability to share knowledge socially; to distribute cognition to others. We aren’t smart because we think, we are smart because we realize that we often do not need to.

Also, because we can write and store knowledge in a physical form, we can accumulate knowledge over time in ways that other mammals cannot.

New essay coming to Risk and Progress soon on this very topic!

Very good piece. This concept is so important to how we understand AI and its potential. It is futile to compare a machine to the "intelligence" of a single human - it is how this technology enhances the network that matters. One small quibble, I think we consistently underestimate the extent and power of networks in pre-industrial societies going all the way back to the hunter gatherers.