Why do we need World Federal Government?

Why the World Needs One Government: A Historical and Technological Case for Global Unity

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

As human civilization advances, the world is growing more interconnected than ever before. Rapid developments in transportation and communication technologies have brought distant populations into regular contact. Flying across continents is routine. Immigration, global commerce, international education, and cross-border cooperation are part of everyday life. In this increasingly integrated world, people are engaging more frequently across ethnic, cultural, and national boundaries. Although racism and tribalism persist, so too does a growing sense of shared humanity.

At the same time, our collective impact on the planet is escalating. Population growth, industrial activity, and unsustainable consumption are straining Earth's ecosystems. Climate change, deforestation, pollution, and biodiversity loss are not confined by borders, yet they threaten all of us. These global challenges are the byproducts of a deeply connected world—but they are not being met with equally global solutions.

The current system of international governance is fragmented and unequal. While cooperation among sovereign states exists, it is often limited by national interests and power imbalances. No single government has the mandate or authority to take decisive, coordinated action on behalf of humanity as a whole.

This is the core argument of this essay: the time has come to establish a Federal Government of the World—one with the legitimacy and responsibility to address global problems while respecting the sovereignty of individual nations. Such a government would not govern people’s daily lives or interfere with local political systems. Instead, it would focus exclusively on transnational issues that no country can solve alone: climate change, nuclear disarmament, and more.

The chapters that follow will explore the historical, technological, and political reasons for this proposal, examine the failures of current international institutions, and present a vision for a limited yet essential world government equipped to meet the challenges of the 21st century and beyond.

2. How Transportation Technology Changed Human Interaction

Human beings have always formed communities based on shared identity—language, culture, religion, or values. These communities, from ancient tribes to modern nations, form the basis for governance. People agree to pay taxes, build shared infrastructure, and support social programs because they feel bound by a sense of mutual belonging and destiny.

What has changed over time is the scale of these communities. In early history, kingdoms and tribes were small, often limited to what one could travel on foot or by horse. But as transportation technologies improved, the scope of human interaction expanded—and with it, so did the size and complexity of political units.

The first major leap came during the Age of Exploration in the 16th century. With the rise of maritime navigation, global trade networks began to form. Merchants traveled across continents, exchanging goods like spices and cotton. This was the beginning of global economic interaction, but it remained the domain of a privileged few.

The Industrial Revolution brought the next transformation. The invention of the locomotive enabled mass transportation. Trains made it possible for ordinary people to travel long distances affordably and reliably. Travel agencies emerged to support the growing demand, introducing group tours, traveler’s checks, and guidebooks. National markets and cultures became more integrated. It is important to note that the impact of railways was not limited to England, their birthplace, but spread to many corners of the globe, as illustrated by the chart below.

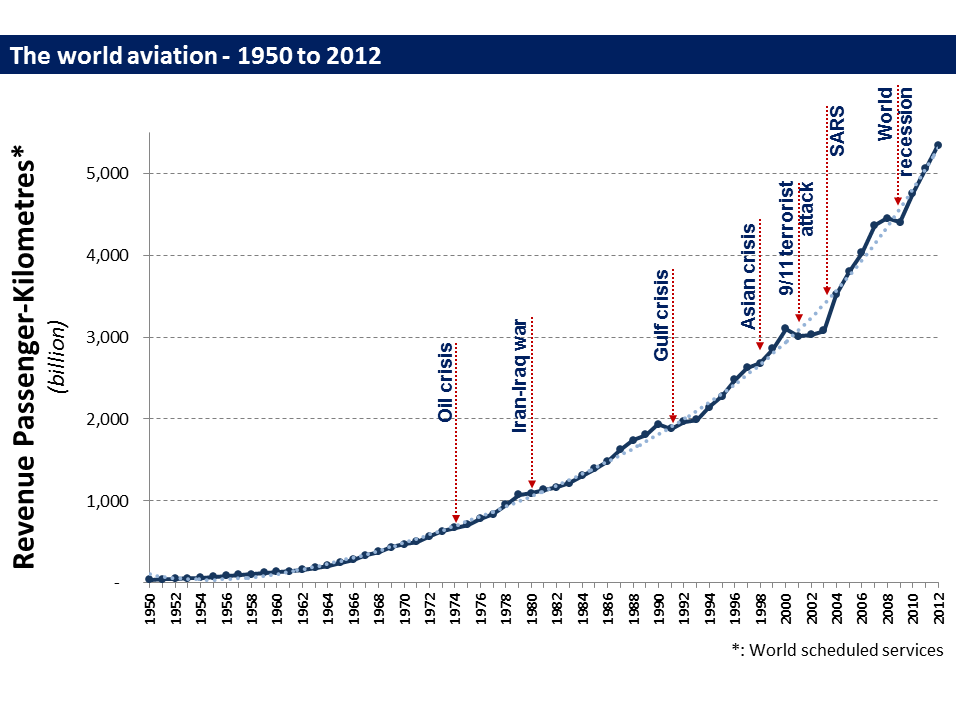

Then came air travel. Since 1995, the global economy, measured by gross domestic product (GDP), has grown at an average annual rate of 2.8%, while worldwide passenger air traffic, measured in Revenue Passenger-Kilometers (RPK), has increased at a faster average rate of 5.0% per year. Unlike trains, which primarily served domestic mobility, airplanes revolutionized international travel. Suddenly, it was possible to cross oceans in hours. The number of international travelers skyrocketed, and with it, so did global awareness and cultural exchange. In 1950, international tourist arrivals were negligible. Today, they exceed 5,000 billion passenger-kilometers annually.

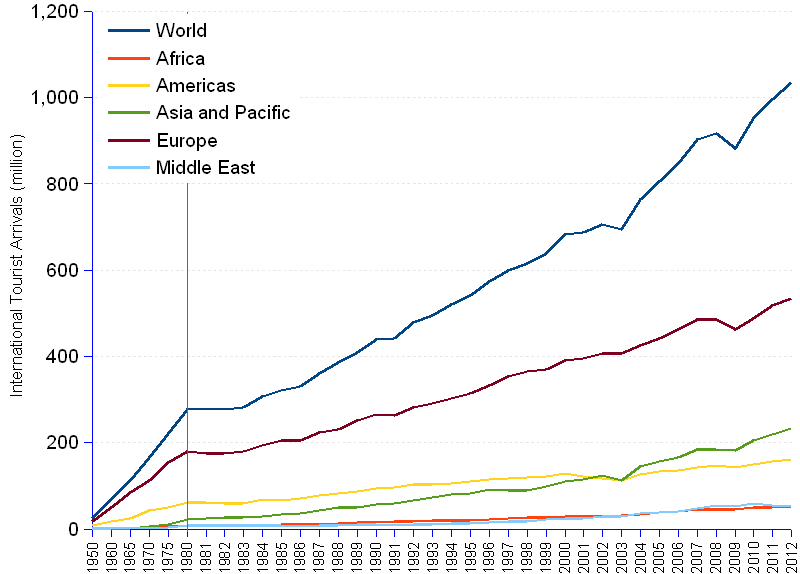

All of these technologies fundamentally transformed human society. Two major changes occurred. First, international travel became widespread. In 1950, international tourist arrivals (ITA) were negligible, but as shown in the chart below, they eventually reached 1.036 billion.

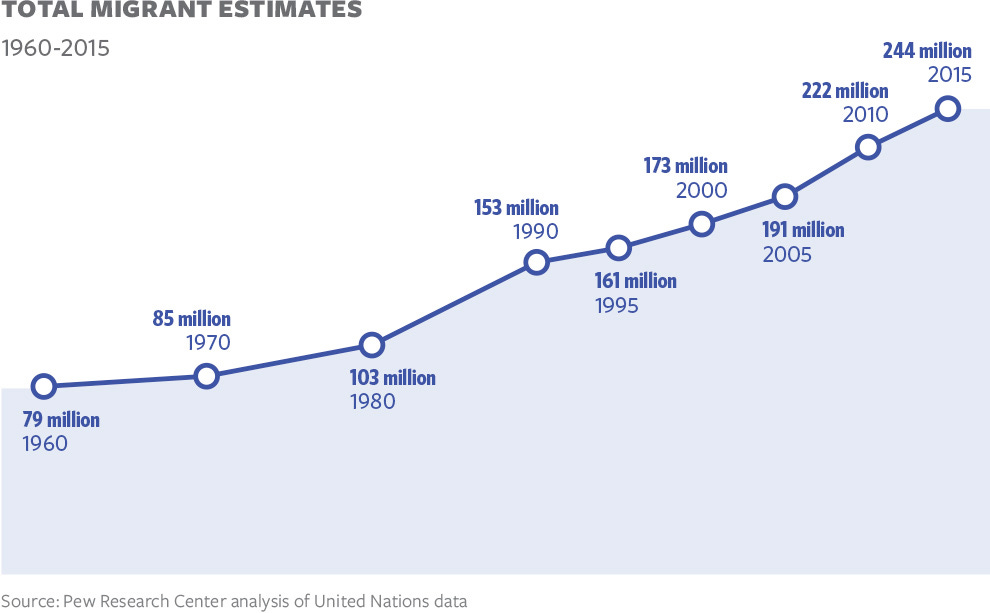

Second, the rise of transportation accelerated international migration. Once dominated by movement from poor countries to wealthy nations like the U.S., migration patterns have diversified. Now countries across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East—such as Germany, the UK, the UAE, and even Asian countries—are accepting immigrants.

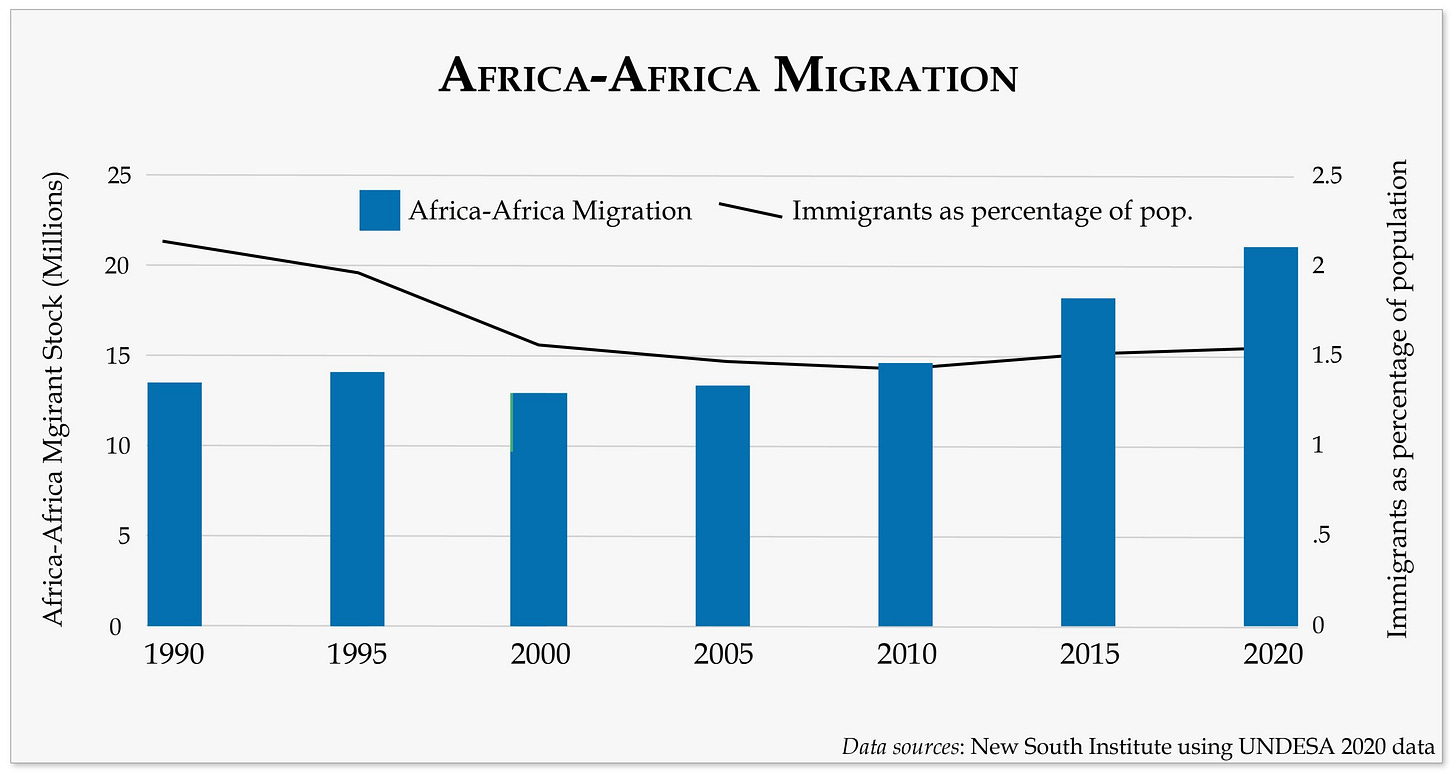

One important trend to note is the rise of a new form of migration. Migration between low-income countries has become increasingly common. For example, the chart below illustrates migration flows to and from African countries.

These changes have had profound social consequences. As people travel, live, and work across borders, they begin to form relationships that transcend national identities. A person might grow up in one country, study in another, and work in a third—sharing their life with colleagues and friends from all over the world.

I’ve experienced this firsthand. Born and raised in Japan, I’ve lived in the United States, Zambia, Chile, and France, and visited around 50 countries. My classmates in college included Indians, Pakistanis, and Americans. Today, I work in Tokyo alongside engineers from across the globe. One close friend is a Taiwanese-Australian working here in Japan. This kind of life, once rare, is becoming increasingly normal.

As our daily interactions stretch across borders, so too does our sense of identity. Just as local communities expanded into nations, global connectivity is nurturing a shared human identity. And just as larger communities once demanded new forms of governance, our global community now requires institutions capable of addressing our common challenges. Transportation technology hasn’t just reshaped how we move—it’s reshaping who we are.

3. The Natural Trend Toward Larger Political Units

a. A historical look at how political boundaries expanded with social and economic integration.

History provides ample evidence that as people interact more—economically, socially, and culturally—they tend to form larger and more cohesive political units. European history, in particular, illustrates this pattern clearly.

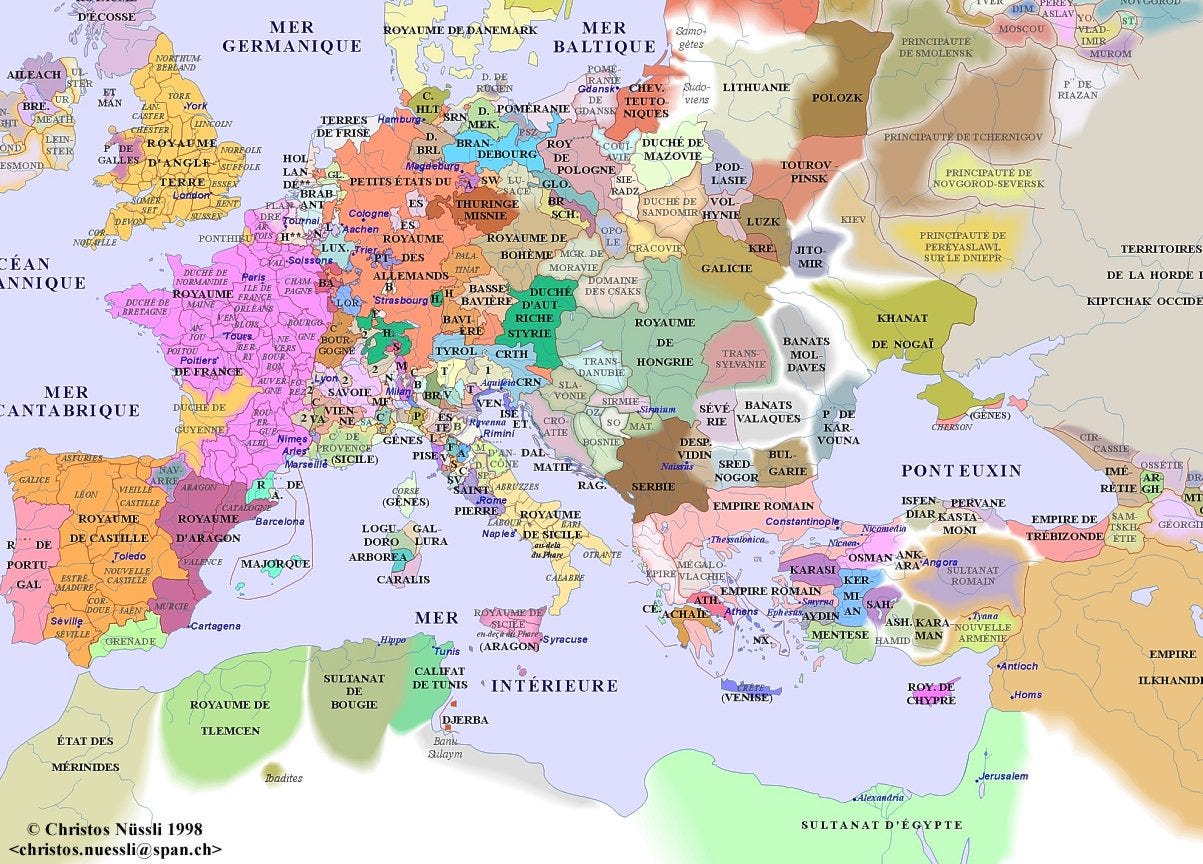

In 1300, Europe was highly fragmented, as illustrated by the map below. Northern Italy and what is now Germany were divided into a patchwork of small city-states, duchies, and principalities. Even England, which by then had unified into a single kingdom, had earlier been composed of several smaller kingdoms known as the Heptarchy. Over time, through warfare, alliances, and increasing economic integration, these fragmented entities coalesced into larger nation-states.

France stands as a key example. Prior to the French Revolution, France had already centralized considerable power under the monarchy. However, it was the Revolution that forged a deeper sense of national unity. The revolutionaries cultivated a strong shared identity among citizens—replacing regional dialects with standardized French, creating national education, and invoking the ideals of fraternity and civic duty. This transformation not only strengthened national cohesion but also redefined the relationship between citizens and the state.

Similar processes unfolded elsewhere. Germany remained politically fragmented until the late 19th century. Before its unification in 1871, the region consisted of numerous kingdoms and duchies, loosely associated through the German Confederation. Yet a shared language, cultural heritage, and rising nationalist sentiment—fueled by military victories and economic integration—culminated in the establishment of the unified Germany.

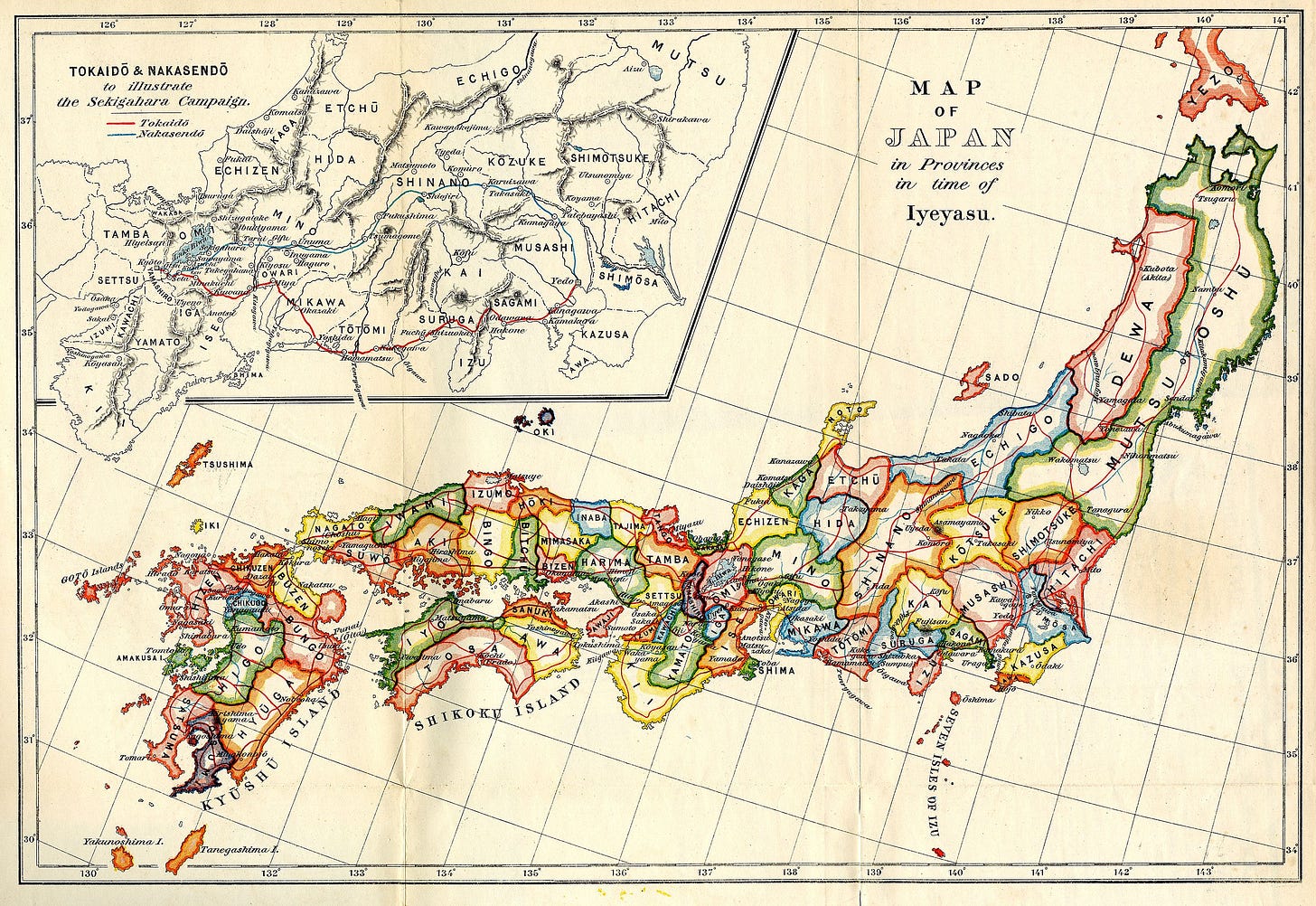

Japan followed a parallel trajectory. In the mid-1800s, it was divided into around 270 feudal domains, each governed by a local lord. While the Tokugawa Shogunate held nominal authority, the domains operated with significant autonomy. As trade and communication increased within Japan, so did the sense of a unified Japanese identity. Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan underwent radical reforms: the feudal system was abolished, a national education system was introduced, and standard Japanese replaced regional dialects. These changes laid the groundwork for a modern nation-state.

Italy, too, transitioned from fragmentation to unity during the same period. Between 1848 and 1871, numerous independent states and foreign-controlled territories were consolidated into the Kingdom of Italy, driven by a mix of nationalist fervor and strategic diplomacy.

Even the United States offers a relevant case. Originally a loose confederation of states, it gradually evolved into a strong federal union. Over time, Americans developed a stronger identification with the federal government, especially as national infrastructure, economic policy, and military institutions expanded.

Across these cases, the pattern is clear: as interaction deepens—through trade, migration, communication, and shared challenges—people come to see themselves as part of a broader political community. This shared identity enables the creation of larger, more integrated political structures.

b. Colonization and the Creation of Larger, Unified States

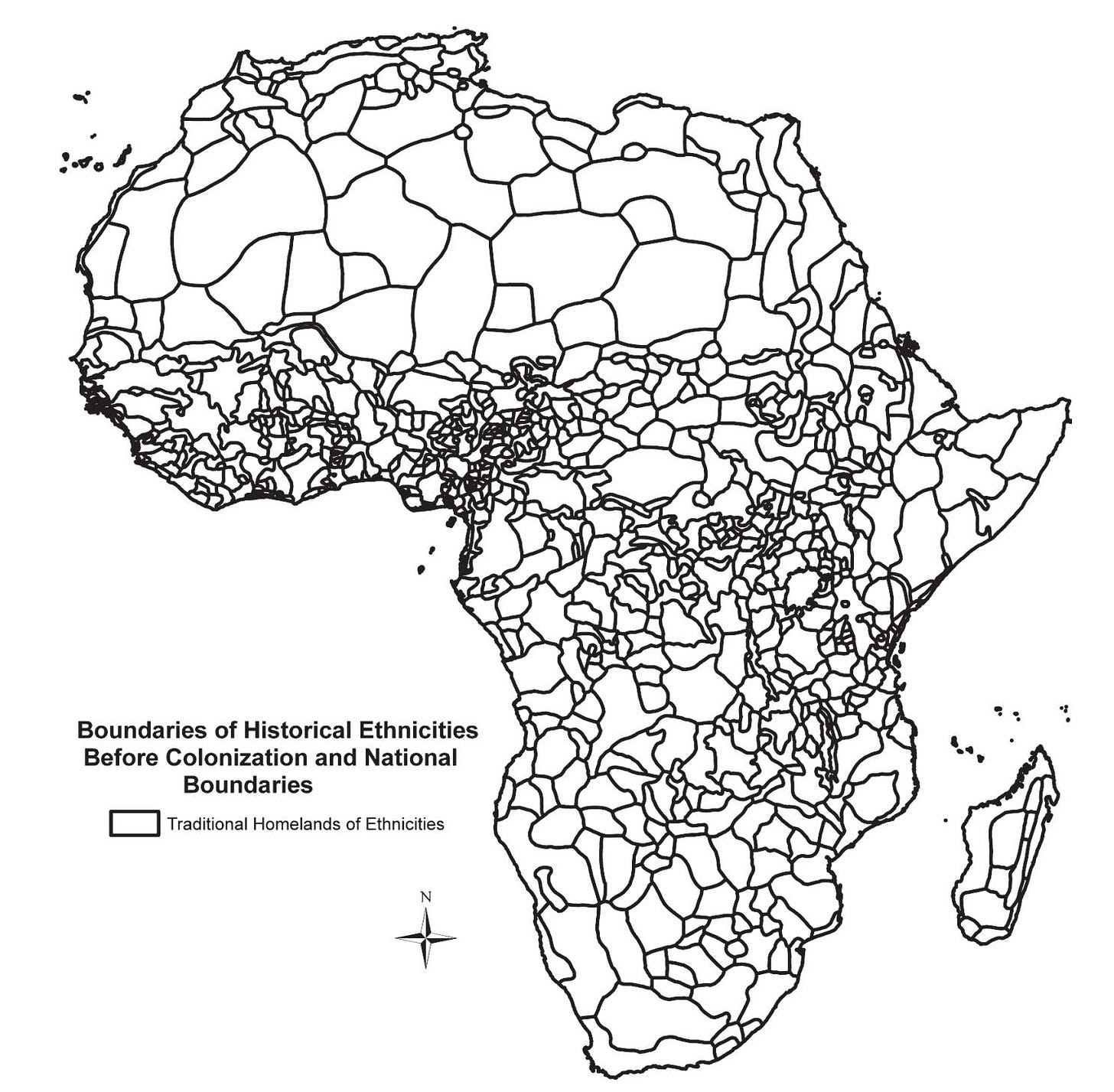

Before the era of European colonization, many regions—especially in Africa, Asia, and Southeast Asia—were composed of small, decentralized political entities. These were often organized around ethnic, linguistic, or tribal lines, and they rarely extended beyond local boundaries. For example, pre-colonial Africa was home to hundreds of distinct ethnic groups and communities, each governing its own territory. The map of Africa before colonization illustrates this striking diversity.

During the 19th century, European powers colonized large parts of the world, redrawing maps to suit their own political and economic interests. In Africa, colonial borders were drawn with little regard for existing ethnic or cultural boundaries. This artificial division forced disparate communities into the same political units while splitting others across different colonies. After independence, most African countries retained these colonial borders. Despite the many conflicts and civil wars that followed, many African states have gradually developed a shared national identity, marking a significant, albeit difficult, step in political unification.

A similar story unfolded in parts of Asia. Indonesia, now the fourth most populous country in the world, was once a collection of separate kingdoms and ethnic groups spread across thousands of islands. Dutch colonization unified these territories under a single administrative system. Post-independence, Indonesia retained this structure and worked to develop a cohesive national identity, even while recognizing its cultural diversity.

India is another example. Historically divided into numerous kingdoms, empires, and princely states, India had not been a single political unit for most of its history. British colonization, while exploitative and destructive in many ways, did lay the groundwork for unifying these territories under a common administration. After independence, India maintained this territorial integrity and established a democratic federal republic.

Myanmar, too, was once a patchwork of distinct ethnic regions and kingdoms. British colonial rule consolidated these areas into a single entity, which later became the modern nation-state of Myanmar. Though the country continues to face severe ethnic and political challenges, it remains an example of how larger political units can be formed under unifying governance.

While many of these unifications were the result of external imposition rather than organic integration, they nonetheless reflect a broader historical trend: the steady enlargement of political communities. Today, people in these countries share a national identity with far more individuals than their ancestors did. This demonstrates an ongoing pattern in human governance—toward larger, more inclusive political structures.

The question now is whether we can extend this trend to the global level, not through conquest or colonization, but through cooperation and democratic consensus. As challenges like climate change and nuclear proliferation transcend national borders, the case for a unified global framework grows stronger.

c. The League of Nations and the Birth of Global Governance

The 20th century marked a turning point in the evolution of political unity: for the first time in history, humanity attempted to create institutions that transcended national boundaries to address global problems collectively. The formation of the League of Nations after World War I was the first serious attempt at establishing a global governing body.

Although the League ultimately failed to prevent the outbreak of World War II, its creation was a radical shift in international thinking. It introduced the idea that peace and cooperation were not solely the responsibility of individual states but of the global community as a whole. The League's failure was not due to the invalidity of the concept, but rather to structural weaknesses—chief among them, the lack of enforcement mechanisms and the absence of key global powers, such as the United States.

After the devastation of World War II, the international community made a second, more ambitious attempt with the founding of the United Nations. The UN has had some notable successes—facilitating decolonization, coordinating humanitarian aid, and promoting international dialogue—but it has also repeatedly struggled to resolve conflicts and enforce international norms, largely because it remains a forum for sovereign states rather than a truly unified global authority.

Despite their limitations, both the League of Nations and the United Nations reflect an unmistakable trend: the growing recognition that some challenges—such as war, poverty, climate change, and nuclear proliferation—transcend national borders and require coordinated global solutions. These institutions are imperfect, but they represent an early stage in the gradual formation of a shared political consciousness at the planetary level.

In this context, the need for a more effective and democratically accountable form of global governance becomes clear. The world has already taken the first steps toward political integration at the global scale. The next step is to build institutions capable of delivering on the promise of peace, justice, and sustainability—not just between nations, but for all of humanity.

4. Why Current Global Institutions Fall Short

The 20th century witnessed the birth of global governance through the creation of international institutions. Yet, the United Nations, the current and perhaps the strongest attempt, suffers from structural flaws that limit its effectiveness. From unequal voting power to the persistent dominance of national interests, current global institutions fall short of the coordinated, democratic, and enforceable governance needed to address the shared challenges of the 21st century.

In the sections that follow, we will examine three core failures of today’s global institutions: the entrenched inequality of the veto system, the dangerous inconsistencies in nuclear governance, and the inability to enforce environmental commitments. These failures highlight the urgent need for a more unified, accountable, and effective global political structure: a Federal Government of the World.

a. The veto privilege and the concentration of power among the Big Five

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC), one of the six principal organs of the UN, holds the primary responsibility for maintaining international peace and security. It passes resolutions, conducts peacekeeping operations, and imposes sanctions meant to uphold global stability. However, its effectiveness is deeply undermined by a structural flaw: the veto power held by its five permanent members—the United States, the United Kingdom, France, China, and Russia.

This veto privilege allows any one of these five countries to unilaterally block any resolution, regardless of global consensus or majority support within the Council. In practice, this means a single nation can override the collective will of the international community, turning the UNSC into what can be described as an oligarchy of superpowers.

A stark example of this dysfunction occurred in 2022, when Russia vetoed a resolution condemning its own invasion of Ukraine. Despite widespread international condemnation and majority support for action, the resolution was blocked, highlighting how the veto can be used to escape accountability and mock the principles of international law.

The problem is not unique to Russia. The United States, for instance, has frequently used its veto to shield Israel from criticism or international censure. Since 2020, the U.S. has cast 14 vetoes, with all but two related to protecting Israeli interests. Historically, as of 2020, Russia and the former Soviet Union had used the veto 117 times, and the U.S. 83 times, with the other three permanent members using it far less often. Still, the pattern is consistent: national interests of powerful states are preserved at the expense of collective security.

Reforming this system is extremely difficult. Any amendment to the UNSC structure requires approval from two-thirds of the General Assembly—and crucially, must also be ratified by all five permanent members. This effectively grants the Big Five the power to block any proposal that threatens their privileged position, including proposals to abolish the veto itself.

This systemic imbalance underscores the urgent need for a new model of global governance. If we are to address the most pressing challenges of our time—war, inequality, climate change, and more—we must build institutions that reflect democratic principles, not outdated hierarchies of power. A Federal Government of the World would offer a structure where no single nation holds absolute power over global decisions, ensuring a fairer, more accountable, and more effective international system.

b. Nuclear Weapons and Double Standards

In 1968, the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council—the United States, the United Kingdom, France, China, and Russia—secured yet another exclusive privilege through the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Under this treaty, these nations were officially recognized as nuclear-weapon states, while all other signatories were designated as non-nuclear-weapon states. The NPT thus formalized a deeply unequal system, where a small group of powerful countries retained overwhelming destructive capabilities.

The justification for this inequality rested on a critical promise: that the nuclear-armed states would pursue disarmament in good faith. However, decades after the treaty’s adoption, this promise remains largely unfulfilled. Instead of working seriously toward disarmament, the nuclear powers have preserved and in some cases modernized their arsenals, undermining the treaty’s spirit and perpetuating global insecurity.

The consequences of this imbalance are particularly dangerous when nuclear states are authoritarian or aggressive. Russia and China, for example, use their nuclear status to exert power and intimidate neighboring countries. A tragic illustration of this dynamic is the situation in Ukraine. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine gave up the nuclear weapons it had inherited, trusting international assurances for its security. That decision, seen at the time as a step toward peace, left Ukraine exposed. In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea, and in 2022, it launched a full-scale invasion. Ukraine’s lack of nuclear deterrence left it with limited means to resist.

This vulnerability reverberates throughout the world. Countries in proximity to nuclear powers find themselves with few options for defense and are in practice forced to turn to other nuclear states—particularly the United States—for protection. This dependence results in foreign military bases, strategic compromises, and financial costs. Japan, Germany, and South Korea, for instance, host the largest contingents of U.S. troops outside American territory. As of recent data, out of 173,000 U.S. troops deployed abroad, approximately 114,000 are stationed in these three nations—strategically positioned near Russia and China.

The financial burden is also significant. Japan alone contributes around $4 billion annually to support the U.S. military presence under the so-called "sympathy budget" (Omoiyari Yosan). This is not to suggest that the United States is coercing its allies; rather, the root problem is the nuclear hierarchy itself. The existence of privileged nuclear states forces smaller nations to seek protection and endure the costs that come with it.

This system entrenches global inequality and fosters geopolitical instability. It is not sustainable to base world security on the dominance of a few and the dependence of many. A just and effective global order requires a new framework—one that eliminates double standards and ensures that no nation wields unchecked power over others. This is precisely why we need a Federal Government of the World: to create a balanced, rule-based international system that prioritizes collective security over national privilege.

c. Environmental Crises and Lack of Enforcement

Despite growing awareness and global dialogue on environmental issues, meaningful progress in combating climate change and ecological degradation remains inconsistent and insufficient. The fundamental reason is structural: there is no binding global authority with the power to create and enforce environmental laws. International cooperation on environmental protection is currently based on voluntary agreements, not enforceable obligations. In short, the world lacks a global government to hold countries accountable.

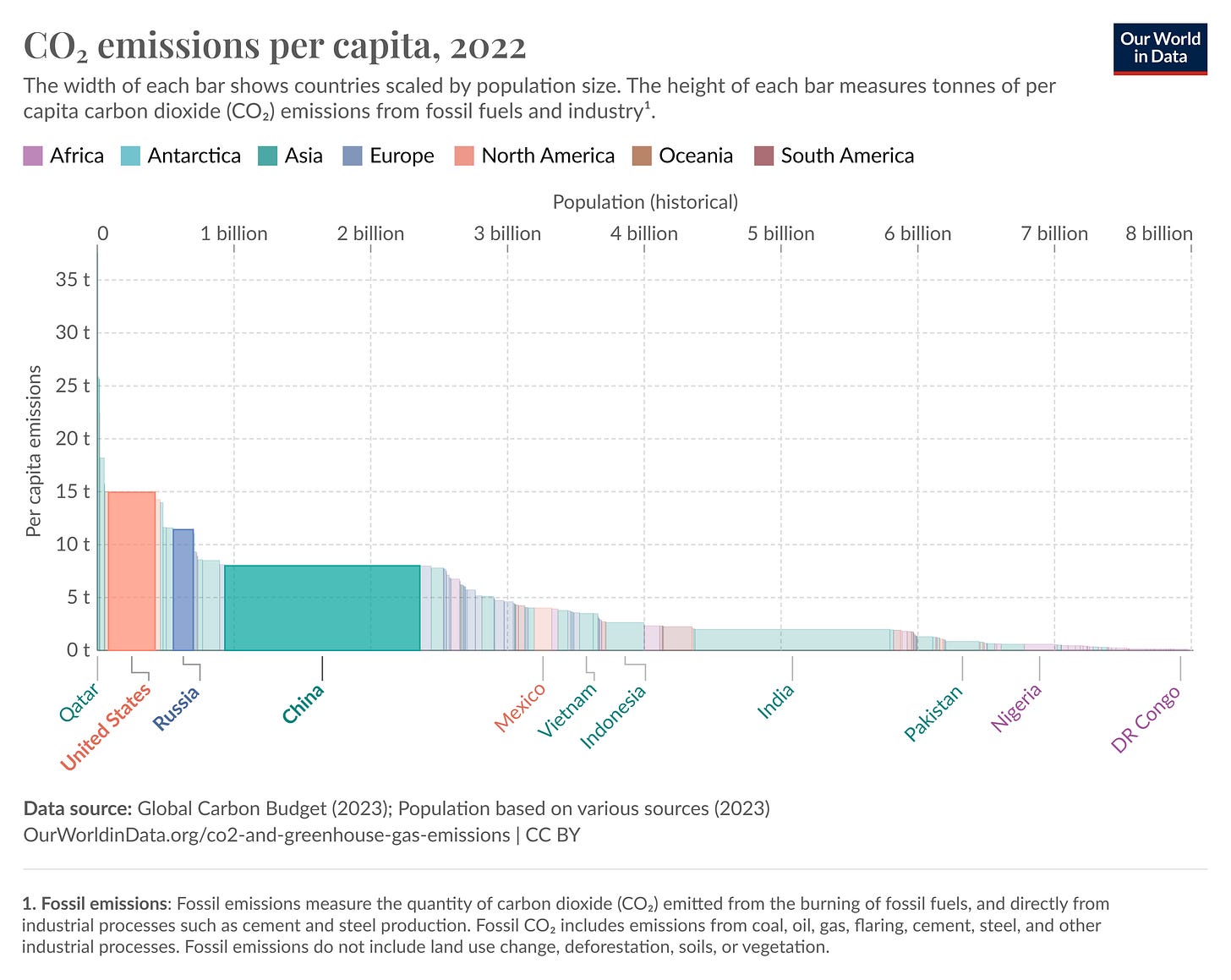

This weakness is most visible in the behavior of the world’s most powerful countries—notably the United States, China, and Russia. These nations are among the largest contributors to carbon dioxide emissions, yet face little real pressure to change course. A revealing chart from Our World in Data illustrates this imbalance. It plots CO2 emissions per capita against total population, demonstrating that countries like the U.S. and China, with both large populations and high emissions per person, dominate global emissions. Together, the two nations are responsible for nearly half of the world’s total CO2 output.

This raises a question of justice: the Earth’s atmosphere belongs to all humanity equally. No country or individual has the moral right to pollute it more than others simply because of economic or military power. The right to emit CO2 should be distributed equally on a per capita basis. Under that metric, nations like the U.S. and Russia far exceed their fair share. While the global average is 4.7 tonnes of CO2 per person annually, the U.S. emits 14.9 tonnes per capita and Russia 11.4 tonnes.

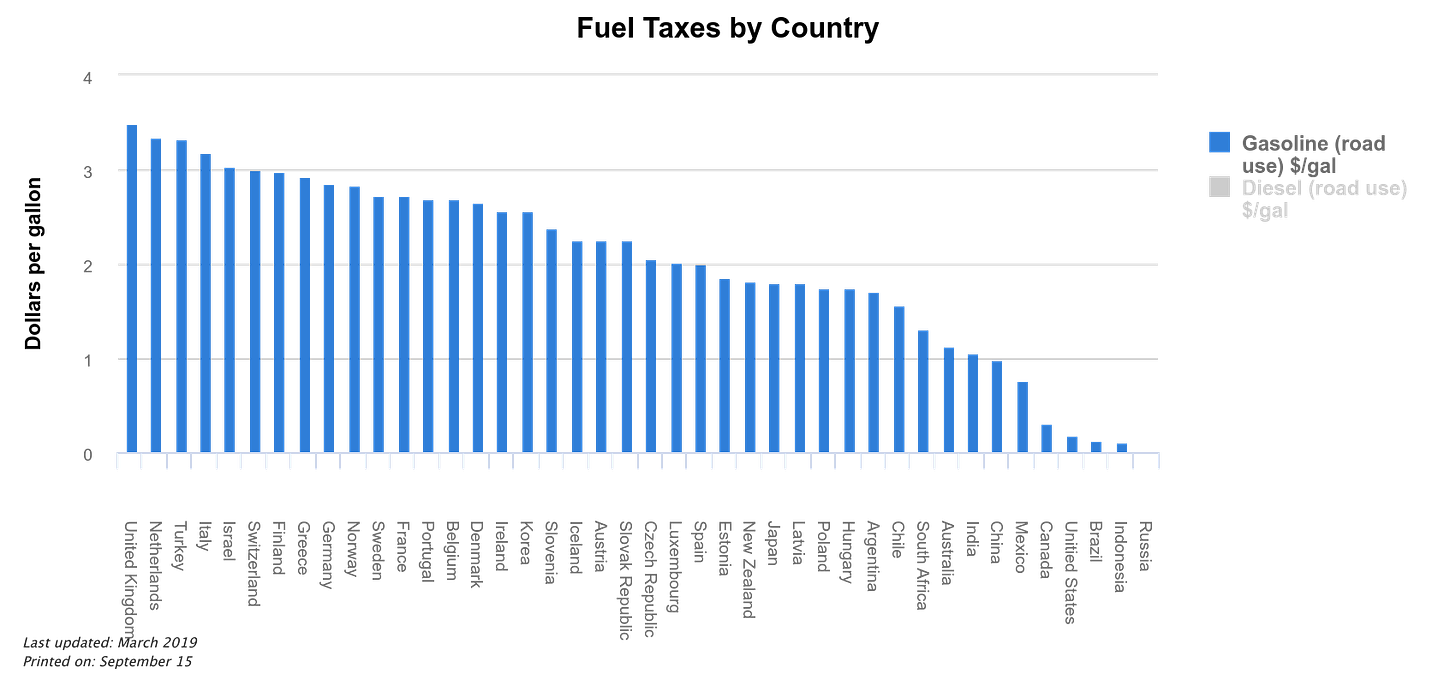

Moreover, countries like the U.S. and Russia fall short even compared to other high-income nations. The average CO2 emissions in high-income countries is about 10.1 tonnes per person. For example, fuel taxes, which serve as a disincentive to carbon-intensive consumption, are significantly lower in the U.S. than in other developed nations. This contributes to a culture of excessive energy use, including widespread reliance on large, fuel-inefficient vehicles.

This disparity is not merely statistical—it reflects structural inequality in global governance. Unlike the veto power at the UN Security Council or the legal structure of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, environmental governance does not formally grant privileges to powerful nations. Yet in practice, their economic and political influence shields them from the fair criticism they deserve.

The solution is both urgent and clear. Humanity must create a global governing body with the authority to pass binding environmental laws and the power to enforce them. This body should be able to impose fines and penalties on nations that fail to meet emissions targets or violate environmental standards. Only through such a unified, enforceable framework can we hope to confront climate change effectively and equitably.

The Federal Government of the World would be that framework. It would represent all humanity equally, ensure fair distribution of environmental responsibilities, and hold all nations—regardless of power—accountable to shared planetary limits. The health of the Earth and the future of our species demand nothing less.

5. A New Vision: Federal Government of World for Global Problems

Throughout human history, advances in transportation and communication have steadily drawn people closer together, fostering shared identities across expanding territories. As social and economic integration deepened, so too did the scale of political units—from tribes to city-states, to kingdoms, to nation-states. This long-term trend reflects a natural evolution toward broader forms of governance, culminating in today’s growing sense of a shared global identity.

Humanity has already attempted to institutionalize this unity through the creation of the League of Nations and, later, the United Nations. These were conceived as steps toward a global governing body, but both have fallen short of the goal. The League collapsed under the weight of global conflict, and the United Nations has been hamstrung by structural flaws, especially the veto power held by the five permanent Security Council members. This has led to paralysis in the face of global crises like nuclear proliferation and climate change.

To address these failures, humanity must now take a decisive step forward: the creation of a Federal Government of the World. This will not be easy. Building a just and effective global authority—one that upholds both equality and diversity—is a challenge with no historical precedent. But two complementary paths offer hope: reforming existing institutions and constructing new ones from the ground up.

One pathway is to reform the United Nations. This would involve eliminating the veto privilege, empowering the General Assembly, and expanding the authority of UN agencies on issues like nuclear disarmament and environmental protection. A vital first step is raising global awareness about the disproportionate power held by the Big Five. Citizens of both powerful and less powerful countries must call out this imbalance—not just by criticizing the privileged nations themselves, but also by holding their own governments accountable for enabling that privilege. A groundswell of informed public pressure can pave the way for genuine institutional reform.

The second pathway is to build a new world government from scratch. This could begin with the expansion of existing NGOs dedicated to the cause of global unity. These organizations could evolve into a democratic, non-profit body with global reach, launching a registration and voting system—secured by technologies like biometric authentication—to allow every person on the planet to participate in decision-making. A system accessible through mobile apps or web platforms could democratize this effort. Once participation reaches a significant threshold—say, 10% to 30% of the world’s population—it could claim legitimacy as a representative institution of humanity.

In either model, enforcement is crucial. Initially, the new global government may lack the resources to maintain its own military. In such a case, enforcement must be delegated to national governments. Over time, as the institution grows, it could develop limited strategic capabilities—for example, precision conventional weapons designed to neutralize law-breaking leadership with minimal collateral damage. Such a capacity would be far less destructive than the large-scale invasions we've seen in recent history.

It is equally important to define what the world government must not do. Understandable concerns exist about losing national sovereignty or imposing uniform standards that erase cultural diversity. These concerns are valid. A responsible global government must restrict its authority to issues that transcend national borders—chiefly security and environmental protection—while respecting the independence and cultural uniqueness of nation-states.

The Federal Government of the World must be limited in scope but firm in authority. It must protect global commons, enforce peace, and uphold a fair and sustainable future for all. By embracing this vision, we do not erase our differences—we protect them, within a just and secure global order.

6. Conclusion and Call to Action

If this essay has resonated with you—even in part—it means you recognize the urgent need for a new form of global governance capable of addressing problems that no single nation can solve alone. Issues such as nuclear proliferation and climate change demand a coordinated, enforceable response beyond the reach of national governments.

Change begins with awareness, but it must lead to action. Here are some practical steps you can take to support the movement toward a Federal Government of the World:

Engage with Your Local Representatives

Write to your elected officials. Inform them about the limitations of national solutions to global problems. Emphasize that a democratic and accountable world government is essential to securing peace, environmental sustainability, and human rights across the globe.Register with the Federal Government of the World

Visit the web site of Federal Government of the World and register your support. This initiative aims to build the foundation for a legitimate world government by gathering global citizens in a shared political system. Your participation strengthens its credibility and influence.Support Like-Minded Organizations

Join or contribute to non-profit groups dedicated to global democracy and federalism:World Federalist Movement: https://www.wfm-igp.org/

Democratic World Federalists: https://dwfed.org/

Citizens for Global Solutions: https://globalsolutions.org/

Start Conversations

Share these ideas with friends, family, and colleagues. Host discussions, write articles, or use social media to raise awareness. Change grows from the ground up when people are informed and motivated.

This is not merely a political proposal—it is a moral and existential imperative. A Federal Government of the World is not about erasing national identities, but about protecting our shared future through cooperation, law, and justice. The responsibility now lies with all of us to turn that vision into reality.

If you have questions, ideas, or challenges to raise, please leave a comment and join the conversation.