Exchangism: How Market Expansion Has Driven Economic Development Throughout History

Economic development has historically been driven by the size of markets, which in turn are shaped by population density and transportation efficiency.

This post is a longer version of an essay on Exchangism. If you want the short version, click here.

Table of Contents

Size of Market, Enterprise, and Specialization

Smithian economic development model: The division of labor is limited by the extent of the market

Enhanced Smithian economic development model: The division of labor is limited by the size of organization

Factors that determine the specialization

Population density

Transportation

Wealth

Size of Business Organization

Jungle

How history evolved around exchange

First Stage: Intra-city trade

Second Stage: The regional trade by water transport

Third Stage: Global trade by enterprise

Large Enterprise Made Possible by Global Market

Factor that determine the size of enterprise: Size of Market and Financial management capability

Effect of Enterprise

Enterprise as labor exchange market

Enterprise as incentive maker

Enterprise as productivity booster

1. Introduction

The Smithian model of economic development proposes that as markets expand, the division of labor increases. This specialization boosts worker productivity, ultimately leading to greater societal wealth. While this model has long influenced economic thinking, it doesn’t fully capture the dynamics of modern development. By adding one crucial element—the size of the organization—we can significantly enhance its explanatory power. Larger enterprises, which arise to meet the demands of expansive markets, can specialize their workforce far more efficiently than smaller organizations, further driving productivity and economic growth.

Market size itself is shaped by several factors, most notably population density and transportation efficiency. When people live close together, they have more immediate access to buyers and sellers. Efficient transportation systems further enlarge the accessible market, making it possible to serve more customers across greater distances.

Larger markets create powerful economic effects. They raise the return on investment (ROI) by allowing fixed investments—such as manufacturing equipment or R&D spending—to be utilized more intensively across a broader customer base. Additionally, the value of intangible assets like brand, software, and intellectual property scales proportionately with market size, further enhancing ROI. This higher ROI attracts more capital, fostering innovation. In large markets, firms also tend to specialize in areas where they hold a comparative advantage, improving overall efficiency. Additionally, larger markets enable only the most productive firms to survive and scale, raising the average productivity of the entire economy.

This essay traces how market size and specialization have historically shaped economic development, divided into three major stages:

Intra-City Trade: The first large markets emerged in ancient cities, where high population density fostered vibrant local exchange and laid the foundations for early civilizations.

Regional Trade by Water Transport: With the advent of ship-based trade, cities and agricultural regions were connected, creating larger regional markets. River transport, in particular, was vital in pre-modern Europe and Japan, allowing goods to travel deep inland and connecting disparate economic centers.

Global Trade and the Rise of Enterprise: Beginning with the Age of Discovery, the world entered an era of global markets. Colonization provided European countries with access to a global market—one of the key reasons the Industrial Revolution began in Europe and why they became the first modern economies. Yet another critical development was the rise of the global enterprise—large-scale organizations capable of mobilizing vast labor forces and investments. Innovations in financial management, such as joint-stock companies and public accounting, enabled better investment oversight, facilitating the growth of these enterprises. Their size allowed for more specialization and higher productivity. Even today, developed economies tend to have a larger share of their workforce employed in big enterprises compared to developing nations.

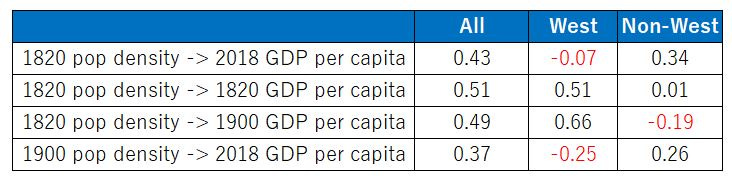

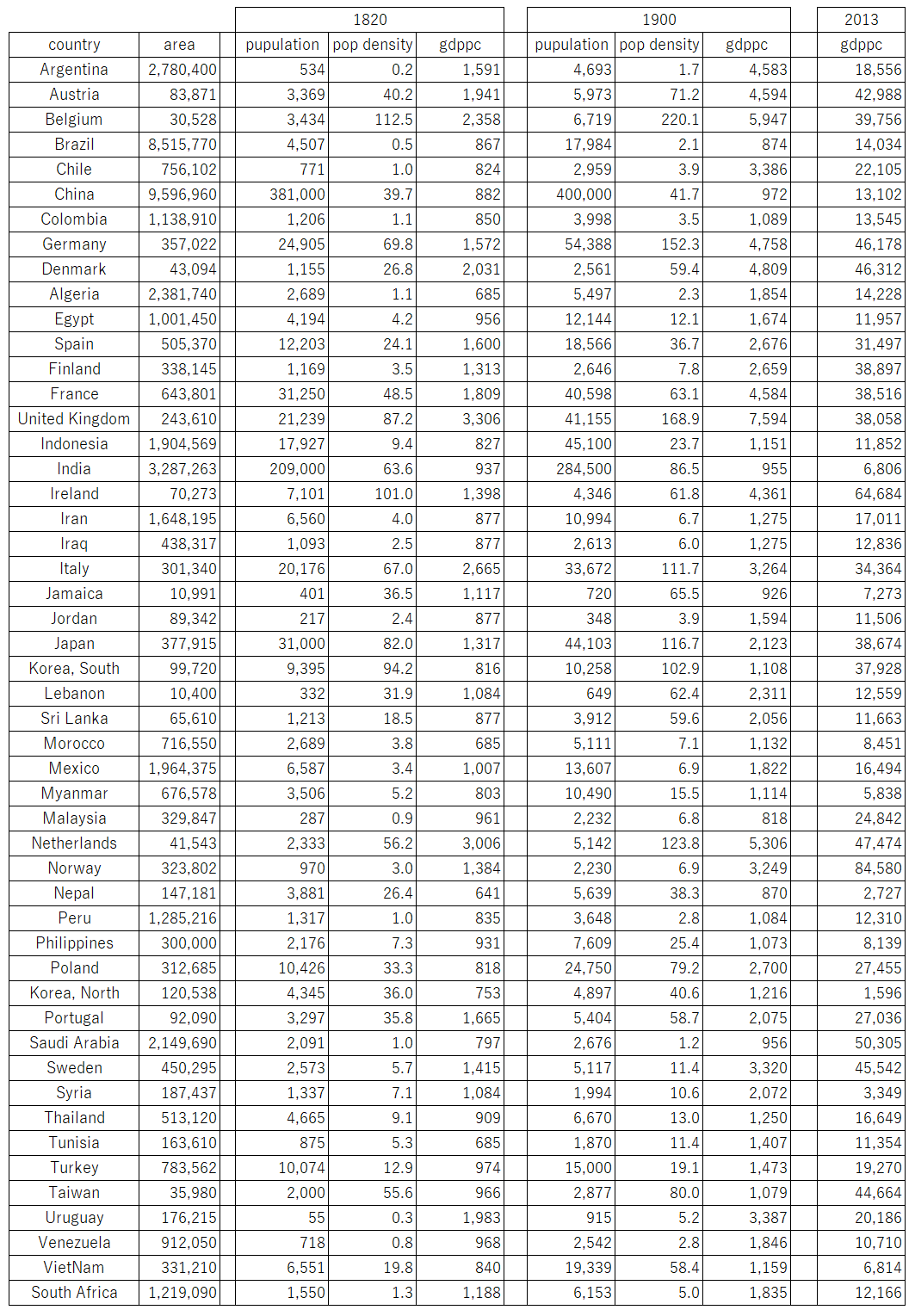

To support this theory, the essay presents statistical evidence linking market size and economic outcomes. Because historical market size data is scarce, population density is used as a proxy. A global analysis using data from 50 countries in 1820, 1900, and 2018 reveals a correlation of 0.43 between population density in 1820 and GDP per capita in 2018. When focusing on Western countries, the correlation rises to 0.66. Notably, 14 of the 20 most densely populated countries in 1900 were developed economies by 2018.

Further support comes from a regional study within China. The correlation between population density in Chinese provinces in 1953 and their GDP per capita in 2023 is 0.61. This internal comparison removes confounding factors like cultural and institutional variation, highlighting the strong impact of population density on development.

Altogether, these findings suggest a compelling link between market size and long-term economic prosperity—the essence of Exchangism.

2. Phenomena That Exchangism Explains

Exchangism offers a unified framework to explain a range of important historical and contemporary economic phenomena. By focusing on the role of market size, enterprise scale, and specialization, this theory helps make sense of why certain regions developed faster and more robustly than others.

The Emergence of the First Civilizations: The earliest complex societies emerged in urban centers. These cities created concentrated markets where goods and services could be exchanged with minimal transportation costs. The dense population allowed for the first real division of labor, kickstarting economic development through expanded exchange.

Why Western Europe and Japan Industrialized First: These regions combined high population density with easy access to maritime and river transport, creating large, efficient markets. This infrastructure allowed for more intensive exchange, which in turn supported the rise of large enterprises and greater specialization—key drivers of early industrialization.

The Development Gap Between Western and Eastern Europe: Western Europe had superior maritime access, enabling earlier and more extensive trade networks. In contrast, many parts of Eastern Europe were landlocked and lacked efficient transport routes, limiting market size and slowing development.

Regional Disparities Within China: Coastal provinces in China are more economically advanced than inland provinces. This is largely due to their access to ocean and river transport, which facilitated trade both domestically and internationally. In contrast, inland provinces, being more isolated and less connected, were slower to develop.

By examining these phenomena through the lens of Exchangism, we gain a clearer understanding of how market conditions and exchange networks have consistently shaped the trajectory of economic development across time and geography.

3. Size of Market, Enterprise, and Specialization

a. Smithian Economic Development Model: The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Extent of the Market

Adam Smith was among the first to articulate a foundational principle of economic development: the extent of the market determines the degree of specialization. In his seminal work, The Wealth of Nations (1776), Smith described the workings of a pin factory, where production was divided into multiple distinct tasks—sometimes as many as 18—each performed by a different worker. For example, producing a pin involved drawing out wire, cutting it, forming the head, attaching it, and packaging the final product. When each worker focused on a single step, total output increased dramatically—by as much as 240 to 4800 times, according to Smith's observations.

Smith identified three key reasons why specialization boosts productivity:

Skill Improvement: Repetition of a specific task leads to greater proficiency. Workers become quicker and more precise through practice.

Reduced Switching Time: Switching between tasks incurs time and mental cost. Specialization minimizes this lost time by keeping workers focused on a single task.

Innovation: Focused workers are more likely to develop tools or techniques to improve their task. Smith gives the example of a boy who, tasked with opening and closing a valve, devised a mechanism to automate the job using a simple rope system—eliminating the need for manual operation entirely.

Crucially, Smith linked the degree of specialization to the size of the market. In small or isolated markets, there isn’t enough demand to justify a highly specialized workforce. For example, in the remote Highlands of Scotland, Smith observed that tradesmen like carpenters or blacksmiths had to perform a wide range of tasks because the market was too small to support niche specialization. He concluded, "It is impossible there should be such a trade as even that of a nailer in the remote and inland parts of the Highlands of Scotland."

This insight forms the core of the Smithian development model: larger markets enable deeper specialization, which leads to greater productivity and, ultimately, economic growth.

b. Enhanced Smithian Development Model: The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Size of the Organization

While Adam Smith's insight—that the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market—laid the groundwork for understanding economic growth, we can build upon this by introducing a critical additional factor: the size of the organization.

As markets expand, demand increases. In response, businesses grow in size to meet this demand. This organizational growth enables a higher degree of specialization internally. Returning to Smith’s example of a pin factory, he observed that in a workshop of ten workers, some individuals had to perform multiple tasks due to limited scale. However, if the market grew larger, the same enterprise could expand its workforce, allowing each worker to focus on just one task. Thus, as the size of the organization increases, so does the depth of labor specialization.

In this enhanced Smithian model, the firm—not just the market—becomes the unit through which specialization is realized. We can therefore revise Smith’s principle to say: "The division of labor is limited by the size of the organization."

History supports this idea. As global markets emerged—especially from the 17th century onward with European colonization and long-distance trade—businesses expanded dramatically. Large enterprises began to dominate production, logistics, and commerce. These firms harnessed the benefits of internal specialization to increase productivity.

Later in this essay, we will explore how advances in financial techniques further enabled firms to scale, enhancing their ability to specialize and boosting overall economic development. This evolution underscores the enhanced Smithian insight: economic growth is not only driven by the size of the market but also by the capacity of organizations to scale and specialize within it.

c. Factors That Determine Specialization

i. The size of the Market

1. Population Density

One of the most fundamental factors that determines the extent of a market is population density. Simply put, when people live closer together, the cost and difficulty of exchanging goods and services is dramatically reduced. In contrast, when potential buyers and sellers are scattered over a large area, transportation costs rise, exchanges become infrequent, and the incentive to specialize weakens.

High population density increases the number of potential customers a producer can reach within a short distance. For manufacturers and service providers, this effectively enlarges their accessible market, justifying investment in specialization and increasing productivity. In other words, dense populations shrink the cost of access while expanding demand.

This dynamic became especially clear with the emergence of cities in ancient times. Urban centers concentrated people in ways that made frequent, diverse exchanges feasible. Cities like those in Mesopotamia marked the rise of early urban civilizations precisely because high population density allowed for market formation, specialization, and surplus-driven commerce. Similar patterns appeared independently in ancient China, the Indus Valley, Mesoamerica, and sub-Saharan Africa. Across all these civilizations, population concentration was a prerequisite for sustained economic development.

Even today, population density remains a powerful predictor of economic vitality. Most of the world’s wealthy regions—Western Europe, East Asia, and parts of North America—are in temperate zones that historically supported dense agricultural populations. Over centuries, these regions developed vibrant trade networks and sophisticated economies built on exchange.

Modern data reinforces this: countries with higher population densities tend to have higher GDP per capita. This correlation also appears within nations. In China, for instance, coastal and riverine provinces with higher population densities consistently show stronger economic performance than sparsely populated inland regions. These relationships will be explored in more detail in the statistical section of this essay.

Ultimately, population density acts as the groundwork for market size, which in turn determines the degree of labor specialization—and by extension, the pace of economic development. In the framework of Exchangism, it is one of the clearest and most enduring examples of how physical conditions shape the potential for prosperity through exchange.

2. Transportation

Alongside population density, transportation is a key determinant of market size and economic specialization. At its core, transportation lowers transaction costs by connecting buyers and sellers across space. When transportation becomes more efficient, the market expands—not just geographically, but also in the diversity of goods and services exchanged.

The benefits of exchange grow as distance increases, especially when trading goods unique to specific regions. Take herring, for example: it is native to the northern seas of Japan and Europe. Demand, however, was often concentrated in southern regions. The only way to meet this demand was through fleets of ships transporting herring over long distances. Because herring was scarce in the destination markets, traders could command high profits. As a result, herring became a major commodity in 15th-century Europe and 19th-century Japan (for more detail, see here for Europe and here for Japan) . The spice trade offers an even more dramatic example. Spices could only be grown in tropical Asia but were in high demand in Europe, where their value justified the immense effort and risk of long-distance sea voyages. This pursuit of high-profit helped launch the Age of Exploration.

Among all modes of transport, water transport has historically been the most efficient. Adam Smith emphasized this, comparing cargo transport between Edinburgh and London: by sea, only 6 to 8 men were needed; by land, 100 men and 400 horses (for more detail, see here) . The cost and efficiency gap was enormous. Smith also noted that many ancient civilizations developed around rivers and coasts, which enabled extensive waterborne trade and thus larger markets.

Historians such as Fernand Braudel expanded on Smith’s insight. Braudel showed that maritime routes, particularly in the Mediterranean during the age of Philip II, carried far more goods than overland alternatives. The Mediterranean Sea functioned as a vast platform for the movement of goods, people, and ideas (for more detail, see this article) .

Two geographic features determine access to water transport: coastline and rivers. Countries with long, meandering coastlines—like Japan and much of Europe—have more land adjacent to the sea, increasing the proportion of their populations living near the ocean. This high ratio of people living near the ocean historically enabled greater economic exchange. In contrast, large continental countries like China and India have relatively short coastlines compared to their landmass, limiting access to maritime trade.

Here are then coastline lengths:

Europe: 80,429 km

Japan: 29,751 km

China: 14,500 km

India: 7,000 km

Despite its small land area, Japan has a much longer coastline than either India or China. Europe, with a similarly sized landmass to China or India, has a vastly longer, more irregular coastline. These features meant that people in Japan and Europe historically lived closer to the sea, giving them superior access to waterborne commerce. Before the rise of modern infrastructure, this advantage translated into earlier and more widespread market development.

Rivers, too, have been crucial to economic development. Most major rivers are navigable, even those with faster currents like in Japan. Many cities in the world such as London, Paris, Wuhan, and Hanoi all emerged as key trading hubs due to their river access. In Europe, rivers like the Rhine and Danube connected vast regions, supporting robust trade networks. In China, the Grand Canal—spanning 1,776 kilometers—linked Beijing and Hangzhou, enabling long-distance grain transport and stabilizing food supply in the capital. In pre-modern Japan, over 70 rivers were used for transporting goods, forming a dense trade network.

Together, rivers and coastlines shaped the economic geography throughout history. Where access to water transport was abundant, markets grew, specialization flourished, and economic development accelerated. Transportation is not just a logistical detail—it is a foundational force behind the rise of prosperity through exchange.

3. Wealth

Income levels play a crucial role in determining the size of a market. Regardless of how many people live in a country, if most of them have very low incomes, their purchasing power remains limited. This means demand for goods and services will be weak, and the incentives for producers to specialize and scale up production are diminished. In contrast, when average income levels rise, individuals can afford to consume a wider variety of goods and services. Even without any change in population, the market effectively becomes larger.

This dynamic was clearly visible during the economic modernization of the 19th and 20th centuries. As poor agricultural workers moved into cities and took on cash-paying industrial jobs, their increased earnings generated new consumer demand. This expansion in purchasing power widened markets for manufactured goods, which in turn encouraged further specialization, investment, and innovation.

In this way, rising income created a feedback loop: more income led to greater consumption, which expanded the market, which in turn spurred more production and economic growth. This loop illustrates a core principle of Exchangism: the relationship between market size and economic development is not solely about population—it is also about how much each person can buy.

Transportation plays a powerful supporting role in this process. Improved transportation not only allows producers to reach more customers geographically; it also helps those customers become wealthier. Better access to transportation enables individuals to access new labor markets, secure better jobs, and participate more actively in the broader economy. As incomes rise, these individuals become more significant market participants.

In other words, the benefits of improved transportation are twofold: it expands the reach of sellers and increases the purchasing power of buyers. This dual effect magnifies the size of the market and accelerates economic development. Wealth, then, is not just a consequence of economic growth—it is a cause of it, especially when viewed through the lens of exchange.

In the world of economics, income is not just a statistic—it is a signal of how deep and strong a market can be. A wealthier population doesn’t just consume more; it drives the engine of specialization, trade, and progress.

4. Size of Business Organization

The size of business organizations increases market size in two important ways. First, large enterprises can transport more goods over longer distances at lower costs compared to smaller firms. This is because large companies can allocate more resources and achieve economies of scale. A producer can either use a transportation company or develop an in-house logistics department. In either case, a society with large enterprises can trade more goods with more people across broader areas.

The second way large companies expand the market is through their internal labor markets. Employees provide services to their employers, but the recipients of these services are often other employees within the same company. For example, if a shoe designer at a shoe manufacturing firm creates a better-looking shoe that sells well, the workers of entire company benefits. If a purchasing manager secures better manufacturing equipment, factory workers benefit and their productivity increase. As the company hires more employees, the number of internal beneficiaries grows. In other words, as the size of a company increases, so does the size of its internal labor market.

5. Jungle

While population density and access to rivers and coastlines are key contributors to market development, natural barriers can significantly hinder economic integration and the expansion of markets. One of the most impactful of these barriers is the jungle.

Dense tropical forests present serious logistical challenges. Constructing roads or railways through thick jungle terrain is costly, labor-intensive, and often unsustainable. Jared Diamond, in Guns, Germs, and Steel, observed that indigenous people in Papua New Guinea rarely traveled far over land due to the difficulty of moving through dense jungle. Instead, they relied heavily on rivers for mobility. Similarly, in the Amazon basin, river networks serve as the primary mode of transportation, while overland travel and trade remain minimal.

These environmental constraints help explain a key puzzle: why Southeast Asia, despite its high population densities and long coastlines, has historically lagged behind East Asia and the West in economic development. In many parts of Southeast Asia, tropical jungles disrupt overland connectivity, fragment internal markets, and make transportation infrastructure difficult to establish and maintain.

From the perspective of exchange, this means fewer opportunities for trade, specialization, and the economic synergies that arise from a larger market. Geography alone does not determine the market size, but when natural features like jungles inhibit movement and exchange, they limit the conditions necessary for sustained economic development.

ii. The size of Enterprise

The size of a business organization plays a pivotal role in determining the level of specialization it can support. In smaller enterprises, workers often have to perform multiple roles. This was evident even in Adam Smith’s famous example of the pin factory, where in less advanced operations, individuals carried out several distinct tasks. Today, this dynamic persists: in small businesses, employees may handle everything from sales to bookkeeping, often without clearly defined responsibilities. This generalist approach limits the depth of expertise any one worker can develop.

By contrast, large enterprises thrive on specialization. In major corporations, roles are divided with precision. For instance, in a large software company where this author once worked, a sales representative might be responsible for only a handful of clients in a single industry segment, allowing for deep expertise in that vertical. Similarly, accountants may focus exclusively on capital expenditures (CapEx) for a specific asset class, while others manage only operational expenses (OpEx). This structure allows employees to cultivate deep knowledge in narrow domains, greatly boosting efficiency and productivity.

However, such finely tuned specialization is only possible when the enterprise operates in a sufficiently large market. Large businesses emerge and grow to meet the needs of a broad customer base. As we’ll explore in subsequent sections, early examples of sizable enterprises appeared in Medieval Europe and Edo-period Japan—both regions where waterways helped unite fragmented markets. Yet it was the rise of global trade, especially through colonial networks, that enabled the birth of truly global enterprises employing thousands.

These vast organizations, by dividing labor into ever more specific tasks, created the conditions for unprecedented gains in productivity. The larger the enterprise, the more it could specialize. The more it specialized, the more efficiently it could produce. And it is this dynamic—scaling up to serve an expanding market—that lies at the heart of economic development from the perspective of exchange.

d. Examples of large markets in history

Measuring historical market size with precision is nearly impossible. It would require detailed data on transportation costs and population distributions over vast distances and time periods. However, we can approximate market size through alternative means, such as analyzing the geographic spread of trading partners and the movement patterns of merchants.

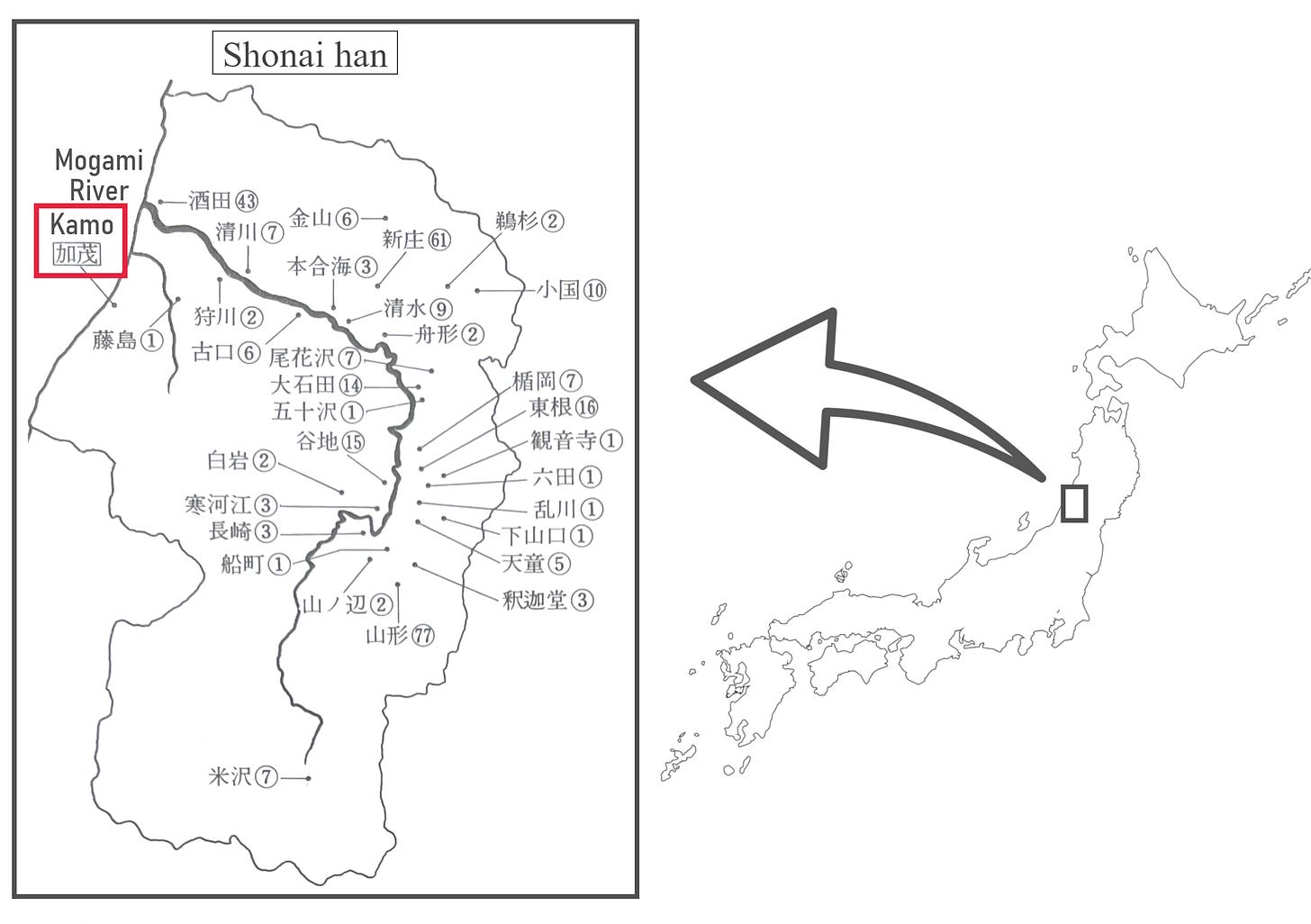

One useful method is to examine historical business records. Consider the case of Kamo, a small port town on the Sea of Japan that thrived commercially in the 19th century. Among its wealthiest merchant families was the Nagasawa family, known for trading general merchandise. Their detailed ledgers in 1809 list the locations and number of their trading partners. These records show that Nagasawa engaged with 366 business partners, most of whom were located along the Mogami River, the region's major waterway. A map based on this data highlights Kamo in red and shows the distribution of partners, with the number of partners in each town indicated in circles.

While exact population figures for these towns are not available, the broader Shonai-han region (through which the Mogami River flows) had an estimated population of about 131,000. Given that the river connected the most densely populated parts of this domain, it's reasonable to infer that Nagasawa's commercial reach extended to a market of around 100,000 people. The river was the primary transport route, underscoring the role of waterborne trade in enabling extensive economic interaction.

Another prominent Kamo merchant family, the Mineda family, offers a broader view of Japan's unified market. Their ledgers reveal trading connections across a much wider area, from Hokkaido in the north to Osaka in the south. A second map based on these records shows customer locations and the number of business partners. This suggests that goods collected in Shonai-han by Nagasawa were later distributed nationwide by Mineda, illustrating how even small, remote towns were integrated into a broader market system via rivers and ocean routes.

This example highlights two key points. First, Japan had one of the highest population densities in the world at the time—fourth after Belgium, Ireland, and the UK, according to the Maddison Project. Given Japan's mountainous terrain, most people lived in narrow coastal plains, making it easier to aggregate supply and demand in compact regions. Second, Kamo was not the endpoint of trade, but a node in a much larger commercial network. This reflects how physical geography—particularly access to water routes—shaped the contours of market size more than political boundaries.

A second way to approximate historical market size is by studying merchant migration and settlement patterns. Ancient Greek traders, for example, established settlements throughout the Mediterranean and Black Sea. A map of these locations shows their coastal concentration, which correlates with the use of ships for transport. These settlements formed the basis of a Pan-Mediterranean trade network that was later unified by the Roman Empire.

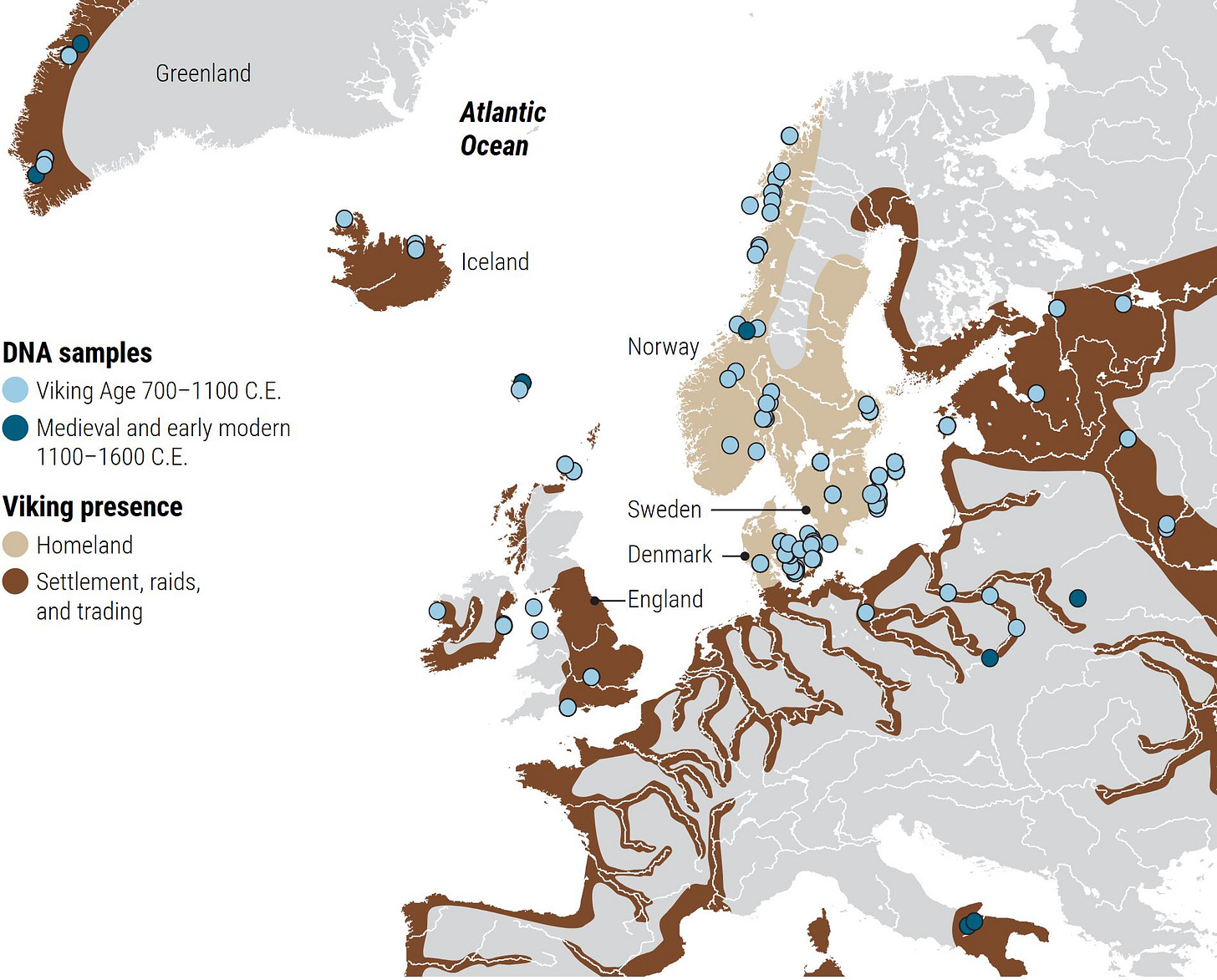

Similarly, the Vikings of the Middle Ages are known not only for their raids but also for extensive trade and settlement. A map of Viking settlements shows how they moved along the coasts and up rivers deep into the European continent. Two key takeaways emerge: first, like the Greeks, the Vikings relied on water routes; second, by navigating inland rivers, they accessed larger populations and expanded their market reach. This connectivity enabled commerce-oriented city-states around the North and Baltic Seas, setting the stage for the rise of regional trade networks.

In all these cases, market size was less a function of political borders and more a result of geographic connectivity. Whether in ancient Greece, Viking-era Europe, or Edo-period Japan, economic integration followed the flow of rivers and seas. The infrastructure of exchange—enabled by natural water routes—defined the boundaries of functional markets long before modern transportation or national economies came into being.

e. Effect of Bigger Market

When population density increase and transport improves, the market become bigger. That means a producer can produce more and sell to more number of customers. That happens to any producer from an individual craftsman and small workshop to large enterprise. When production increase, several positive effects take place.

i. Higher ROI and more investment

One of the primary effects of a larger market is an increase in return on investment (ROI), which encourages more investment across various sectors. Here, investment should be understood broadly: it encompasses any action taken to improve future economic outcomes. This includes acquiring new knowledge or technology, purchasing equipment, building infrastructure such as canals or railways, or even funding scientific research.

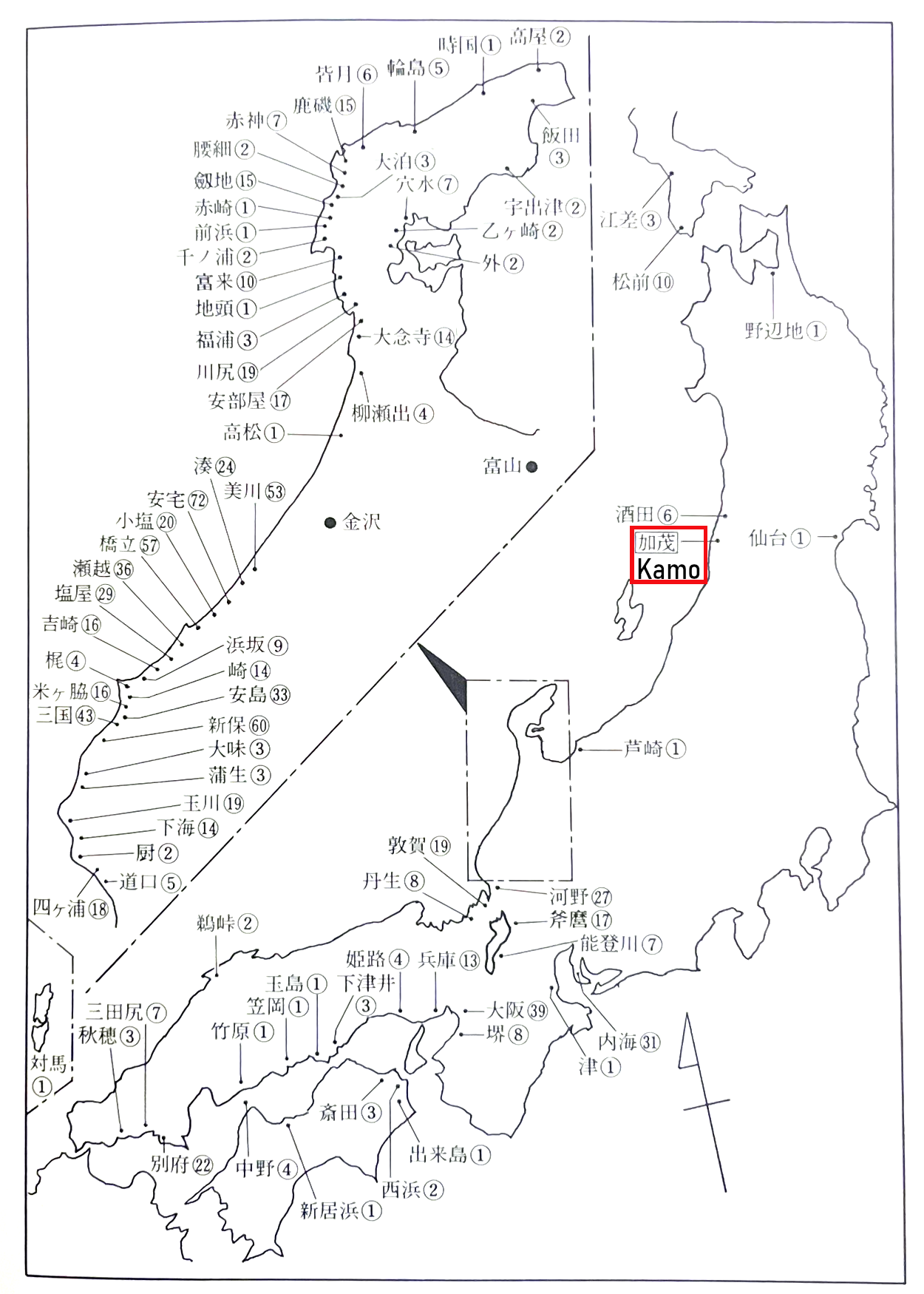

Whether or not such an investment is undertaken depends on its expected return. For businesses, this typically means whether the investment will result in increased revenue or reduced costs. Consider a hypothetical example:

Suppose a company generates $100 million in revenue with total costs of $90 million. It identifies an investment opportunity: a machine that reduces electricity usage and could cut operational costs by 10%. The machine costs $200 million and has a lifespan of 20 years. That means an annual depreciation cost of $10 million. A 10% reduction in expenses would save the company $9 million per year. Since the annual cost of the machine ($10 million) exceeds the expected annual savings ($9 million), the company would likely reject the investment.

Now, imagine the market grows and the company expands by 30%, reaching $130 million in revenue and $117 million in costs. The same 10% cost reduction would now save $11.7 million annually—surpassing the $10 million annual depreciation cost of the machine. In this scenario, the investment becomes profitable and would likely be approved.

This example illustrates a key principle of Exchangism: expanding markets create more viable investment opportunities. As market size increases, more investments cross the profitability threshold, unlocking capital deployment that was previously unjustifiable.

(Note: The table below compares the cost savings and depreciation costs before and after market expansion.)

ii. More innovation

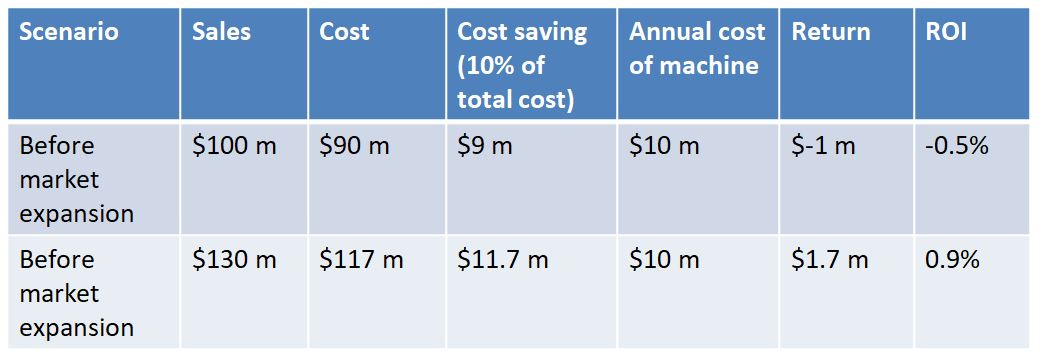

Research and development (R&D) is a form of investment, and like all investments, its feasibility depends on the expected return. A crucial factor in determining that return is the size of the market. Simply put, the larger the market, the greater the potential reward from successful innovation.

Consider an R&D project requiring a $3 million investment, expected to increase a company’s annual sales by 1% for the next five years. For Company A, with $100 million in annual sales, this equates to an extra $1 million per year, or $5 million over five years. For Company B, with $50 million in sales, the same 1% increase brings only $0.5 million per year, or $2.5 million in total. In this case, Company A will likely find the project worthwhile, while Company B may not. Thus, companies operating in larger markets are more inclined and more able to invest in innovation.

(Note: The chart below shows R&D expenditures by company, highlighting that those with larger markets and revenues allocate significantly more to innovation.)

This relationship also makes intuitive sense. As markets grow, producers are better able to meet increasingly diverse and nuanced customer needs through specialized products and services. For example, a small knife workshop that scales up can hire more craftsmen. With more staff, each can specialize—one in kitchen knives, another in hunting knives—enhancing both efficiency and quality. The same principle applies to large enterprises: greater production volumes justify the creation of entirely new production lines for new product categories, leading to better product-market fit and improved customer satisfaction.

History repeatedly demonstrates this pattern. In 19th century England, the expansion of markets due to colonization—particularly the export of textiles to India—transformed Manchester into a hub of cotton manufacturing. To meet demand, companies introduced a wave of innovations that significantly boosted productivity. The surge in raw material transport between Liverpool and Manchester created an opportunity: railways. To serve this growing transportation need, investors funded the world's first railway line. In this way, market expansion catalyzed a chain reaction of innovation, central to the Industrial Revolution.

A modern parallel is the rise of the smartphone. When Apple introduced the iPhone, it didn’t just create a product—it created a massive new market. This market fueled the rapid expansion of industries such as component manufacturing, app development, battery technology, and telecommunications. Each new improvement attracted more users, expanding the market further and sustaining continuous innovation.

Traditional heavy industries offer another example. Henry Ford revolutionized car manufacturing in the early 20th century. One of the reasons for his success was that the United States was already the largest automobile market in the world—likely two to four times larger than that of the UK, France, or Germany. This demand enabled Ford to implement assembly-line production, slashing costs and launching the era of mass production.

Today, the leading edge of innovation is dominated by global corporations operating in global markets. These firms spend vast amounts on R&D, as the chart below shows. They apply innovations not only to develop new products but also to enhance existing ones, increasing their value to consumers. They can do this efficiently by leveraging existing customer relationships and distribution networks.

There is one thing to note here. Some people think that it is small start-ups that make disruptive innovation. It is true that many start-ups brought many innovation especially in IT industry often transforming the industry and even society itself. But these start-ups started their operation small at the beginning and grew quickly. Yet, when they created innovative products, they are already large companies. For example, when Microsoft introduced Windows 95, probably the most impactful product in the company’s history, it has $6 billion in sales and 17,800. When Apple started to sell Macintosh in 1983 or iPhone in 2007, they had about 5 thousands or 21 thousands employees respectively. The founders of these companies were hard working and innovative, so produced good products and made profit from the begging. But it was only after they became large enterprises that they introduced truly innovative products.

iii. Specialization of enterprise into comparative advantage

Comparative advantage is a foundational economic concept. It refers to the ability of an individual or country to produce a particular good or service at a lower opportunity cost than others. This principle helps societies achieve higher total output by allowing individuals to focus on what they do best and then trade for everything else. The same logic applies to enterprises.

Companies, like individuals, have unique strengths. One company may be particularly skilled in wholesale logistics, while another excels in direct-to-consumer retail. In a small market, both companies might have to do everything themselves, limiting efficiency. But as the market expands, the scale allows them to specialize: the wholesale-focused firm can concentrate on bulk purchasing and distribution, while the retail-focused firm can dedicate itself to customer service and sales. They collaborate through exchange, leveraging their respective advantages. This not only increases total output but also improves the quality and efficiency of the entire supply chain.

A good historical example of this is the Nagasawa and Mineda families mentioned earlier. The Nagasawa family specialized in purchasing goods from villages throughout the Shonai region, while the Mineda family focused on long-distance wholesaling of those goods. Each family concentrated on its comparative advantage, and through cooperation, they helped build a more efficient and expansive trade network.

This kind of specialization is particularly visible in modern supply chains and global trade networks. For example, a multinational electronics firm may focus on R&D and branding while outsourcing component manufacturing to a company with superior production technology and cost efficiency. In turn, that component supplier may source raw materials from another firm with specialized access or extraction capabilities. Each link in the chain is focused on what it does best, and the result is a more productive, innovative, and competitive industry overall.

In sum, market expansion enables companies to specialize based on their inherent strengths, not just at the individual worker level but across entire organizations. This leads to more efficient production, better products, and greater economic output.

iv. Winner-take-all effects

(This effect primarily applies to market expansion driven by improvements in transportation.)

When transportation networks improve, markets become more integrated, allowing producers to reach a broader customer base. This increased accessibility intensifies competition across regions. In such an environment, less productive or higher-cost producers struggle to survive and are often pushed out of the market. As a result, only the most efficient and competitive firms remain, raising the overall productivity level of the industry.

Moreover, the surviving firms benefit from economies of scale. With access to a larger market, they can increase production volumes, reduce per-unit costs, and reinvest in further efficiency gains. This dynamic creates a "winner-take-all" effect, where a few high-performing firms dominate the market.

A clear historical example of this occurred in Germany with the advent of the railroad. Before railways, small breweries operated independently in many local towns, each serving a limited area. Once rail transport allowed beer to be shipped efficiently across regions, breweries with better pricing and quality gained a competitive edge. These firms expanded their distribution networks, while smaller, less efficient breweries were forced out. The result was a more concentrated and productive brewing industry.

In essence, transportation-fueled market growth doesn’t just increase access; it reconfigures entire industries around their most efficient players. This process accelerates productivity gains and is a key engine of economic development.

4. How History Evolved Around Exchange

a. First Stage: Intra-City Trade

Period: From the earliest urban settlements to the end of the Middle Ages

Region: Cities worldwide

Characteristics of Exchange: Drastically reduced transaction costs due to physical proximity

Size of Business Organization: Individual or workshop

Market Size: Confined within the city

Before cities emerged, human populations were scattered across small, isolated settlements. Even where some village-level interaction occurred, the small population size and high transportation costs limited trade. At best, modest exchanges took place—perhaps a skilled individual crafted arrowheads or a strong member of the group led construction efforts. But these interactions were too limited in scale to foster true occupational specialization, and as a result, productivity remained low.

The rise of cities marked a turning point. Urbanization slashed the transportation costs of exchange. While transporting goods between settlements was expensive and inefficient, moving goods within a city became trivial by comparison. A skilled knife-maker in a city now had access to exponentially more potential buyers. This proximity meant a larger market size for every specialized producer—whether blacksmiths, cobblers, or bakers.

This market growth triggered a feedback loop: greater specialization led to the creation of more specialized goods and services, which were often superior to generic alternatives. For instance, blacksmiths might craft tools specifically designed for agriculture or construction, increasing efficiency in those sectors. As farmers and builders adopted these specialized tools, demand for them grew, expanding the market for toolmakers and encouraging even more specialization.

Ancient civilizations are often remembered for their grand temples and opulent rulers, but behind these symbols stood a foundation of skilled labor. Civilizations required artisans: stonemasons for temple construction, toolmakers for those masons, tailors for rulers, weavers for clothing, and others who supplied the tools and materials they needed. Each layer of this economic web reflected deepening specialization made possible by intra-city exchange. While improvements in agriculture and the existence of surplus are commonly cited as reasons for the rise of civilization, the explosion of urban trade and specialized labor was equally vital.

Later, large empires and dynasties rose across continents. However, it's important to distinguish between political and economic boundaries. A vast empire did not automatically equate to a large, integrated market. In places like inland China and India, where water transport was scarce, overland trade remained expensive and inefficient. As a result, despite the wide reach of empires, intra-city trade often remained the dominant form of exchange. In such cases, the effective market size—what mattered for economic specialization—was still relatively small.

b. Second Stage: Regional Trade by Water Transport

Period: From Greek civilization to the Middle Ages

Region: Greek civilization, Roman civilization, Indian Ocean Islamic trade, Medieval European trade (North Sea and Baltic Sea trade, Levant trade), Intra-Japan trade during Edo period

Characteristics of Exchange: Long-distance trade by maritime and river transport

Size of Business Organization: Family enterprise

Market size: Regional

Following the formation of cities, the next major driver of economic growth was the emergence of regional trade networks, made possible by advances in efficient water transportation. Societies that leveraged water routes became prosperous and culturally advanced, as efficient trade connected larger populations and facilitated economic specialization across regions.

Merchants who had access to navigable rivers and coastal waters were able to extend their commercial reach far beyond the confines of any one city. As a result, regional markets emerged, encompassing multiple cities and towns connected by shipping routes. These networks enabled the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies across broader areas and were instrumental in creating economically vibrant zones.

Examples of such regional trade-based development include the ancient Mediterranean economies of Greece and Rome, the Indian Ocean trade dominated by Islamic merchants during the medieval period, and Europe’s trade hubs around the North Sea, Baltic Sea, and Levant. Japan’s Edo-period economy also flourished through internal coastal trade. In each of these cases, the expansion of markets supported increasingly complex economies and spurred developments in finance, science, and education.

i. Mediterranean Civilization

The first major leap in regional trade began in the ancient Mediterranean, where geography provided a natural advantage. The region’s abundance of coastlines and islands, especially in areas like Greece and Italy, offered numerous ideal ports. Unlike inland-heavy regions such as China, India, Africa, or the Americas, much of the land around the Mediterranean had direct access to the sea, enabling low-cost maritime trade.

The earliest drivers of this trade were the Phoenicians, followed by the Greeks, and eventually the Romans. As these civilizations expanded, they established robust maritime trading networks that reached their peak under the Roman Empire. Roman prosperity depended heavily on trade across the Mediterranean. For example, much of the food supply for the city of Rome, which reached a population of one million at its height, came from North Africa and was shipped to the port of Ostia before being transported inland.

The goods exchanged were not limited to staples like food, clothing, and leather but included luxury items such as ivory and pearls, sourced from distant regions. This long-distance trade supported a vast and interconnected economy.

While sea transport remained the backbone of Roman commerce, the Romans also developed one of the most advanced road systems in the ancient world. These roads served primarily to connect ports to inland settlements—a role similar to how modern logistics solves the "last-mile" problem. This integration of sea and land transport allowed Roman merchants to extend their reach to villages deep in the interior, incorporating rural producers into the broader economic system. Effectively, the Roman Empire functioned as a unified economic zone.

(Note: The map below illustrates the diversity of goods produced throughout the Empire and the way maritime routes were linked with land transport, showcasing the integrated nature of Roman trade.)

The strategic importance of trade was also reflected in Roman policy. The Empire maintained a powerful navy to protect shipping lanes from pirates and built lighthouses to ensure safe navigation. These measures underscore the critical role maritime trade played in sustaining Roman economic life.

The efficiency of the water trade meant that Mediterranean cities were much closer to Rome than their physical distance would suggest. To illustrate this, consider that Adam Smith estimated shipping to be around 14 times more efficient than land transport. Using this ratio, transporting goods from Carthage to Rome (a distance of about 599 km) was equivalent in cost to moving them just 43 km by land. Applying the same logic, Alexandria (2,120 km away) and Constantinople (1,371 km) were effectively only 152 km and 98 km away, respectively, in cost-adjusted terms. These were shorter than the overland distance to Naples, just 187 km from Rome. In essence, thanks to maritime trade, Rome was economically closer to major Mediterranean cities than to its nearby inland regions.

The name "Mediterranean" literally means "the sea in the middle of the land," and it lived up to this name as perhaps the first truly integrated large-scale market in human history. At its height, the Roman Empire housed 20–25% of the global population, many of whom actively participated in commerce. The capital alone had a population exceeding one million—a scale Europe would not see again until the 19th century. Moreover, the urbanization rate in the Roman Empire (estimated at 20–25%) was higher than in Europe until the modern era. These figures highlight the extraordinary size and integration of the Roman market, which remained unparalleled until the advent of modern global trade. It is a prime example of how market expansion, driven by efficient exchange networks, can underpin sustained economic development.

ii. Indian Ocean Islamic trade

The next major phase of regional maritime trade emerged in the Indian Ocean during the Middle Ages. Starting around the 7th century, Islamic merchants began navigating the waters of the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea. Over time, they extended their reach across a vast maritime network that spanned the East African coast, the Indian subcontinent, and Southeast Asia.

This expansive trade network gave rise to new cultural and linguistic developments. On the East African coast, for instance, prolonged trade between Arab merchants and local populations led to the emergence of Swahili—a lingua franca that blended Arabic with native African languages. The economic and cultural integration was so deep that many coastal communities in Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia adopted Islam, spread largely through peaceful trade rather than conquest.

Islamic merchants also ventured as far as southern China. Historical records show that Muslim communities established themselves in key trading ports like Guangzhou, where they were granted their own residential districts. During the Yuan Dynasty, Muslims even held administrative roles overseeing trade in important ports such as Quanzhou. These developments point to the existence of a market that far exceeded the scale of a city.

iii. North Sea and Baltic Sea trade, Levant trade

Europe's geography offered unique advantages for trade-driven economic development, aligning perfectly with the principles of Exchangism. With its extensive coastlines, peninsulas, and navigable rivers, Europe enabled efficient water transport that connected both coastal and inland regions. Cities like London and Paris flourished as trading hubs thanks to their access to major rivers, while the Rhine served as a vital artery for commerce for centuries. Maritime and riverine routes were not separate but deeply intertwined, dramatically expanding the scope of regional markets.

In medieval Europe, two major trade regions emerged: the Levant trade in the south and the North Sea–Baltic Sea trade in the north. Each played a crucial role in market expansion and specialization.

The Levant trade began to flourish around the 10th century and reached its peak during the Crusades. Italian city-states like Venice and Genoa established maritime dominance, creating direct links between Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean. These routes brought spices, silk, and other luxury goods into Europe, but they also included staples like grain. This trade not only spurred urban growth and wealth accumulation in Italian cities but also fueled intellectual and artistic movements such as the Renaissance. It exemplified how an expanding market stimulates investment, innovation, and cultural dynamism.

In northern Europe, the Baltic and North Sea trade zones rose to prominence around the 11th century. The development of these routes led to the formation of free trading cities, which later organized into the Hanseatic League—a powerful economic and political alliance. By the 14th century, the League could wage and win wars against monarchies like Denmark, underscoring the strength that economic integration could provide.

The goods traded in the northern markets were mostly essential commodities: grain, timber, wool textiles, and fish. This commerce supported broad-based economic integration. Farmers and rural producers became part of a wider network, linking local economies to a broader pan-European market. This expansion enabled greater specialization and higher productivity across regions.

iv. Intra-Japan Trade During the Edo Period

Japan in the late Edo period (1603–1868) offers another compelling case study for Exchangism, demonstrating how internal maritime and riverine trade can unify a national market and stimulate economic development. Despite its relative isolation from global trade networks during this period, Japan developed one of the most integrated domestic economies in the pre-modern world.

Geographically, Japan possessed an extensive and intricate coastline—longer than that of any European country—dotted with numerous natural ports. These ports supported a flourishing domestic maritime trade network. Coastal shipping routes connected all major regions of Japan, while river systems extended this connectivity deep into inland areas. At the center of this network was Osaka, the commercial capital of the time, which functioned as the nation's primary hub of goods exchange and price formation.

This national trading system dramatically expanded the effective market size. The Edo period saw the rise of a wide variety of professions, services, and industries, fueled by the scale and specialization made possible through exchange. Shipbuilding thrived, and financial institutions matured. One of the most remarkable examples of market sophistication was the Dojima Rice Exchange in Osaka, which began trading rice futures as early as 1730. This made it the world's oldest known futures market, predating the Chicago Board of Trade by over a century.

Information flow was equally advanced. A network of signal flags transmitted market data rapidly from Kyushu in the south to Edo (modern-day Tokyo) in the east. This allowed merchants and investors to make informed decisions, increasing market efficiency and fostering speculative activity.

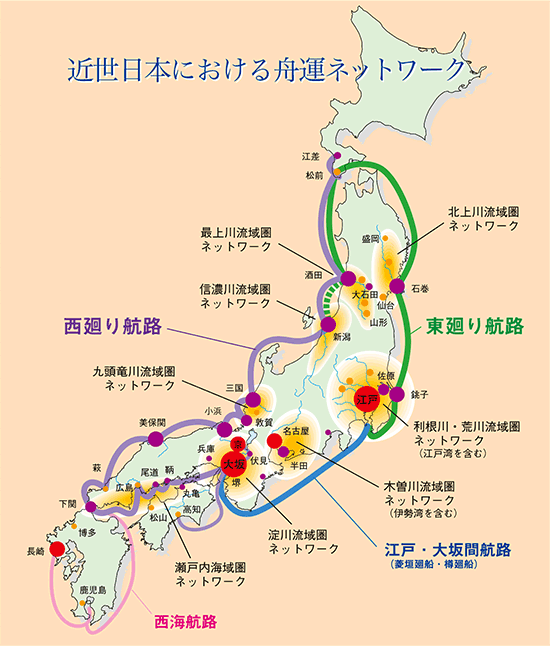

The map below illustrates Japan's 18th-century water transportation network. Thick lines represent maritime routes connecting the entire archipelago, while yellow areas show the reach of river transport. At that time, Japan's population was larger than that of any European country except France. With this combination of high population density and highly developed transport infrastructure, Japan functioned as one of the largest and most integrated national markets in the world.

Importantly, Japan stands out historically as one of only two regions—alongside Western Europe—to have modernized independently, without colonial imposition or external reform. This reinforces the central claim of Exchangism: that the formation of large-scale, integrated markets through efficient internal exchange mechanisms is a critical driver of economic modernization. Japan's Edo-era experience shows that even without external trade, a well-connected internal market can produce complexity, innovation, and institutional development on par with early modern Europe.

c. Third Stage: Global Trade by Enterprises

Period: Early Modern to Modern Era

Regions: Western Europe and East Asia

Characteristics of Exchange: Trade conducted by large-scale corporations enabled by modern transportation and financial systems

Size of Business Organization: Global enterprise

Market Size: Global

The third stage of economic development was marked by the rise of global trade facilitated by enterprises. Emerging in the Early Modern era, this period saw the transition from regional to global markets.

With international trade expanding rapidly after the Age of Discovery, large-scale operations became necessary. Joint-stock companies such as the British and Dutch East India Companies emerged to manage the immense capital and coordination required. These enterprises were backed by growing financial systems that introduced risk management, asset securitization, and sophisticated third-party investment to support global commerce.

Trade infrastructure evolved in parallel. Trading posts, canals, railroads, ports, and warehouses made long-distance trade more efficient. Two transportation revolutions defined this stage: the creation of global maritime routes linking Europe with the Americas, Africa, and Asia; and the development of domestic networks, like railroads and canals, connecting inland regions with coastal trade hubs.

These advancements integrated vast populations into unified global markets, dramatically lowering transaction costs and promoting price convergence. As a result, the economic landscape transformed, laying the foundation for modern capitalism.

i. Age of Discovery and Colonial Economy

The Age of Discovery marked a turning point in global commerce, initiating a truly worldwide market. European powers, driven by exploration and profit, extended their trading networks across oceans. Though reliant on maritime transport like in earlier periods, the scale of operations during this era was unprecedented.

One key factor was the rise of third-party investment. Voyages such as those of Columbus and Magellan were funded by monarchies and powerful banking families. This era also witnessed the birth of joint-stock companies, with the Dutch East India Company becoming an early model of a multinational corporation. Backed by advanced financial systems, these companies could mobilize enormous resources, enabling large enterprises to access vast markets. This allowed for a new degree of labor specialization and organizational scale.

Another defining feature was the integration of the European market, which created sustained demand and high prices for goods like spices. Because Europe functioned as an integrated economic zone, spices imported from Asia could be widely distributed and sold at high prices. If Portuguese or Dutch ships returning from Southeast Asia had been limited to selling spices only to their domestic markets, demand would have been quickly satisfied. But these spices were transported and sold all over Europe, making the trade profitable for a long time. These high margins made long voyages financially viable despite the risks. Crew members and investors alike were incentivized by the potential for extraordinary returns, which often outweighed the dangers of disease, malnutrition, and conflict.

Thus, the Age of Discovery enabled large enterprises to operate across borders, raised labor specialization to new heights, and transformed global trade into a powerful engine of economic growth.

ii. Transportation and the Industrial Revolution

Transportation infrastructure played a pivotal role in enabling the Industrial Revolution by expanding market access to a broader population. For much of history, rivers served as the main arteries of inland transport. However, their reach was geographically limited. The development of canals dramatically expanded this network, linking previously isolated areas and reducing transportation costs.

Europe spearheaded modern canal construction, with notable early developments in Venice, the Netherlands, and France. A landmark example was the Canal du Midi, completed in 1681, which connected the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean. This canal spurred economic activity along its route, boosting wine production in regions like Bordeaux and Languedoc and facilitating long-distance trade between France's interior and global markets.

England soon followed, entering its "Canal Age" between 1760 and 1830. The Bridgewater Canal, opened in 1761 to carry coal from Worsley to Manchester, halved the price of coal in the city by drastically lowering transportation costs. Over this period, Britain built over 4,000 miles (6,400 kilometers) of canals, bringing the benefits of cheap and efficient water transport to areas far from the coast.

As Adam Smith observed, inland regions historically lacked access to wider markets due to their separation from ports and navigable rivers. Before canals, goods had to be transported overland by horses or on foot, which was slow and expensive. Canals solved this problem, integrating inland populations into national and global trade networks. In Britain—a country already engaged in international commerce—this meant that even rural populations became part of the global economy. This integration was a key condition that enabled the Industrial Revolution to emerge first in England.

The inland parts of the country can for a long time have no other market for the greater part of their goods, but the country which lies round about them, and separates them from the sea coast, and the great navigable rivers.

Adam Smith

Technological advancements like the spinning jenny, which required minimal space and labor, made it possible to distribute production into rural areas. Inputs like cotton were transported inland by canals, while finished goods could reach global markets. For the first time in history, the rural worker in England could participate in a global economic system. British cotton products, produced inland, were sold in vast overseas markets such as India. Thus, a rural spinner in Yorkshire could be economically linked to consumers across the globe.

This infrastructure expansion continued into the era of railroads. The 1830 opening of the Manchester-Liverpool Railway marked a turning point, proving the commercial viability of rail. The ensuing "Railway Mania" of the 1840s was fueled by widespread public investment through stock markets—an extension of the same financing mechanisms used for canals. By 1848, Britain had more than 8,000 kilometers of railways connecting its major cities. Continental Europe and the United States quickly adopted similar models, accelerating their own industrial development.

The Industrial Revolution was also a process of transportation development. In earlier periods, only those living near coasts or rivers had access to efficient transport. The construction of canals and, later, railways extended that access to populations far from natural waterways. These new infrastructures enabled people far from river or coast to engage in large-scale production and long-distance trade. Goods such as cotton textiles were transported all the way to Asia, integrating rural economies into what became the largest market economy humanity had ever seen.

The unprecedented size of that market required equally large enterprises. To meet global demand and build massive infrastructure like railways and steel mills, companies in the West had to grow. These larger enterprises employed more workers, used more capital, and became increasingly specialized and sophisticated. Workers within these organizations also became more specialized, focusing on narrower tasks with greater efficiency. In short, the Industrial Revolution was not only a technological and transportation revolution—it was also an organizational revolution.

iii. Large Enterprise Made Possible by Global Market

1. Factor that determine the size of enterprise: Size of Market and Financial management capability

As markets expanded, producers needed to serve a growing number of customers. To meet this demand, they had to scale up production by building larger enterprises. Larger enterprises, in turn, required greater organizational capacity and more effective use of resources.

In earlier times, when businesses employed only a handful of workers and relied solely on the owner's capital, management was relatively straightforward. But as enterprises grew to employ dozens or hundreds of workers and began using third-party funds, financial management became a critical function. Accounting practices enabled businesses to measure success through profit, identify inefficiencies through cost analysis, and manage operations at scale. Without accurate financial information, large-scale operations would have been impossible.

The foundations of modern financial management were laid in 15th-century northern Italy. Italian merchants were actively engaged in long-distance trade across Europe, and banking flourished to support this activity. The Medici family, one of the most influential business families of the era, managed multiple branches across Europe and employed hundreds of workers. During this time, it also became common to separate investors from business operators, especially in commercial voyages. For example, in a unilateral commenda contract, a financier provided all the capital while a merchant executed the trade journey. Profits were split—three-quarters to the financier, one-quarter to the merchant. This arrangement demanded accurate accounting to calculate and verify profit.

To meet this need, merchants developed sophisticated bookkeeping practices. Luca Pacioli's 1494 treatise Summa de Arithmetica described the accounting systems used by northern Italian merchants, including double-entry bookkeeping and the creation of balance sheets—methods that remain foundational today. These innovations enabled complex and geographically dispersed business operations, proving essential to Italy's economic success at the time.

The same principles reappeared at a larger scale in the early 17th century with the founding of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602. The VOC was the world’s first joint-stock company and marked a major milestone in financial history. Its structure separated ownership and management while allowing shares to be publicly traded through the newly created Amsterdam Stock Exchange. This enabled the company to raise unprecedented levels of capital and support operations spanning from Europe to Asia. At its peak, the VOC employed about 60,000 workers and operated 150 ships. These workers were highly specialized—shipbuilding alone involved multiple tasks such as carpentry, maintenance, and dock work, while merchants focused on specific routes and goods like spices, textiles, or tea.

Despite its pioneering role, the VOC eventually collapsed in 1799. The downfall stemmed from limitations in governance and accounting. Widespread corruption, embezzlement, and the absence of internal controls plagued the organization. There was no concept of corporate governance, and its accounting systems were inadequate for measuring profitability across diverse product lines. As a result, the VOC failed to notice declining profits in the spice trade and missed growth opportunities in textiles. These weaknesses underscored the need for more advanced financial management, a lesson that would be taken up in the UK and the US during the Industrial Revolution.

The next wave of financial innovation came with the rise of the railway industry. Railroads required massive upfront investment in tracks, stations, locomotives, and carriages. Because these investments yielded no immediate profit, many investors were reluctant to participate. The introduction of depreciation helped solve this problem by spreading the cost of long-term assets over their useful lives. This accounting method made the financial performance of capital-intensive businesses more transparent and acceptable to investors.

Railways also presented unprecedented complexity in operations. Companies managed a wide array of assets with varying depreciation schedules and recorded multiple revenue streams such as passenger tickets and freight services. The resulting financial statements became too complex for laypeople to understand, leading to opportunities for fraud. One notorious example was George Hudson, the so-called "Railway King," who was accused of paying dividends out of capital rather than revenue, undermining investor trust.

In response, the accounting profession evolved rapidly. Public accountants and accounting firms began verifying financial statements, ensuring transparency and preventing fraud. This external auditing built investor confidence and encouraged further investment. Simultaneously, accounting standards began to emerge—covering practices like depreciation schedules, cost allocation, and revenue recognition. These standards enabled investors to compare companies and detect anomalies. Many of today’s leading accounting firms, such as Deloitte, Price Waterhouse, Ernst & Young, and KPMG, were established during this era.

In sum, financial management capability directly influenced the number and size of enterprises in a society. As accounting practices matured, they enabled complex industries like railways to operate at large scale, manage tens of thousands of employees, and attract capital from a wide range of investors. This organizational capacity, in turn, facilitated higher levels of specialization, further boosting productivity. Without these financial innovations, the Industrial Revolution’s transformative impact on the global economy would not have been possible.

2. Effect of Enterprise

Enterprises enable employees to specialize, which increases overall productivity. Larger enterprises amplify this effect by allowing for deeper and more complex specialization. Numerous studies show that worker productivity is significantly higher in large firms than in small ones. (for example you can find here and here.) As a result, developed countries typically have a higher share of their workforce employed in large firms compared to developing countries. (for example, you can read here and here.) Understanding the effects of large enterprises is therefore crucial to analyzing their role in economic development and societal transformation.

a) Enterprise as labor exchange market

In a small business—such as a workshop where a few craftsmen each make nails in their own way—there is limited specialization and cooperation. But as an organization grows, workers become increasingly specialized. Eventually, the enterprise develops dedicated divisions such as human resources, sales, R&D, and manufacturing. At this stage, we can view the enterprise as an internal labor market: each worker, acting on behalf of the company or its owners, both provides services to and receives services from others within the organization.

For example, an engineer creates a product design and hands it off to the manufacturing team. The manufacturing team produces the product and supplies it to the sales team. The marketing department prepares sales tools and market research to help sales representatives be more effective. Meanwhile, accountants deliver performance data to executives to support better decision-making. In this way, every employee is both a service provider and a service recipient within the enterprise’s internal labor ecosystem.

When we look at a company through this lens, a larger enterprise represents a larger internal labor market. This scale allows for greater specialization and higher productivity. Take, for instance, an HR specialist who designs a compensation plan. If well-structured, it motivates employees, enhances performance, and contributes to increased output. In a company with 100 employees, the impact is limited to that group. In a company with 1,000 employees, the same effort affects ten times more people, magnifying its value.

This logic applies across departments. A marketing team that improves sales efficiency by 5% generates 5 more units of sales in a company with 100 units of output, but 50 more units in a company with 1,000 units. Thus, as enterprise size increases, the internal labor market grows, enhancing both the scope of specialization and the returns to each employee’s contribution. This is a key mechanism by which large enterprises drive productivity and economic development.

b) Enterprise as incentive maker

Incentives play a central role in shaping human behavior. They influence not only how hard a person works, but also the choices they make about how to apply their efforts. Fundamentally, an effective incentive is determined by two key factors: the size of the potential benefit and the certainty of receiving that benefit in return for one’s labor.

Consider a peasant living in a remote, sparsely populated area. Their incentive to work harder is limited by both of these factors. First, the market for selling surplus produce is weak due to poor transportation infrastructure and low population density. Without reliable access to exchange, additional harvest brings little cash income—only more food, which offers diminishing returns compared to the utility of money. Second, even if the peasant attempts to increase production, success is uncertain. Land is often inherited and cannot be easily expanded, and agricultural yields depend heavily on weather conditions. As a result, the marginal benefit of additional labor is both low and uncertain, which discourages extra effort.

Contrast this with a city worker who exchanges 100% of their labor for income. For them, the relationship between effort and reward is more direct and reliable. If they work 20% longer, they can reasonably expect a 20% increase in output and, correspondingly, income. Their work environment is more stable and less affected by external factors like weather. This illustrates the stark difference between a subsistence-based society and an exchange-based economy: the latter offers much stronger and more predictable incentives to be productive.

The rise of large enterprises institutionalized and standardized these incentives. As businesses grew to employ hundreds or thousands of workers, it became necessary to formalize compensation structures. Standardized pay systems reduced uncertainty and created predictable incentives. One of the earliest solutions to this challenge was the salary table, which linked pay to job roles and tenure.

Evidence of early standardized compensation systems can be found in Medieval Italy. Merchants and bankers in cities like Florence, Venice, and Genoa kept detailed records that often reflected tiered wage structures based on job type, skill, and experience. While not as formalized as modern payroll systems, these early records showed the beginnings of structured incentive design.

In Japan during the 18th century, the Mitsui merchant house implemented a more advanced and formal salary system. At its peak, Mitsui employed around 700 workers, organized under multiple managerial layers. Entry-level workers typically began as unpaid apprentices, living in the shops and starting work around age 10. After about seven to eight years, they began to receive pay, which then increased gradually based on years of service and rank. Historical records from Mitsui reveal detailed salary tables dating back to the early 1700s. These tables not only structured incentives but also fostered long-term commitment and motivation. Competition was fierce—only 20% to 30% of apprentices advanced to paid positions—further reinforcing the incentive to work diligently.

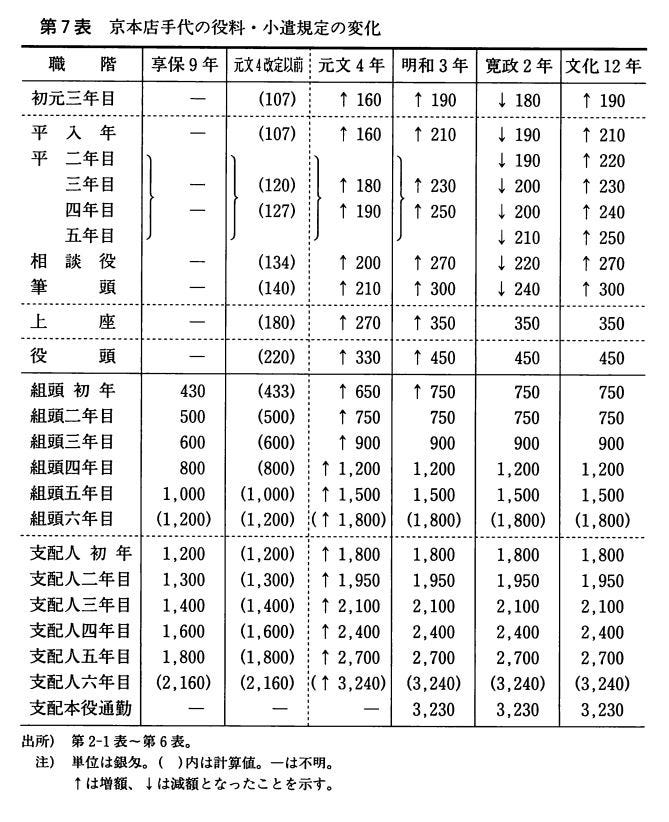

The table below shows the salary table for different years. The left column shows job rank and seniority level, with seniority shown from top to bottom. The six columns are the salaries for different years in era name. "享保9年" on the left means 1724, and "文化12年" on the right means 1815.

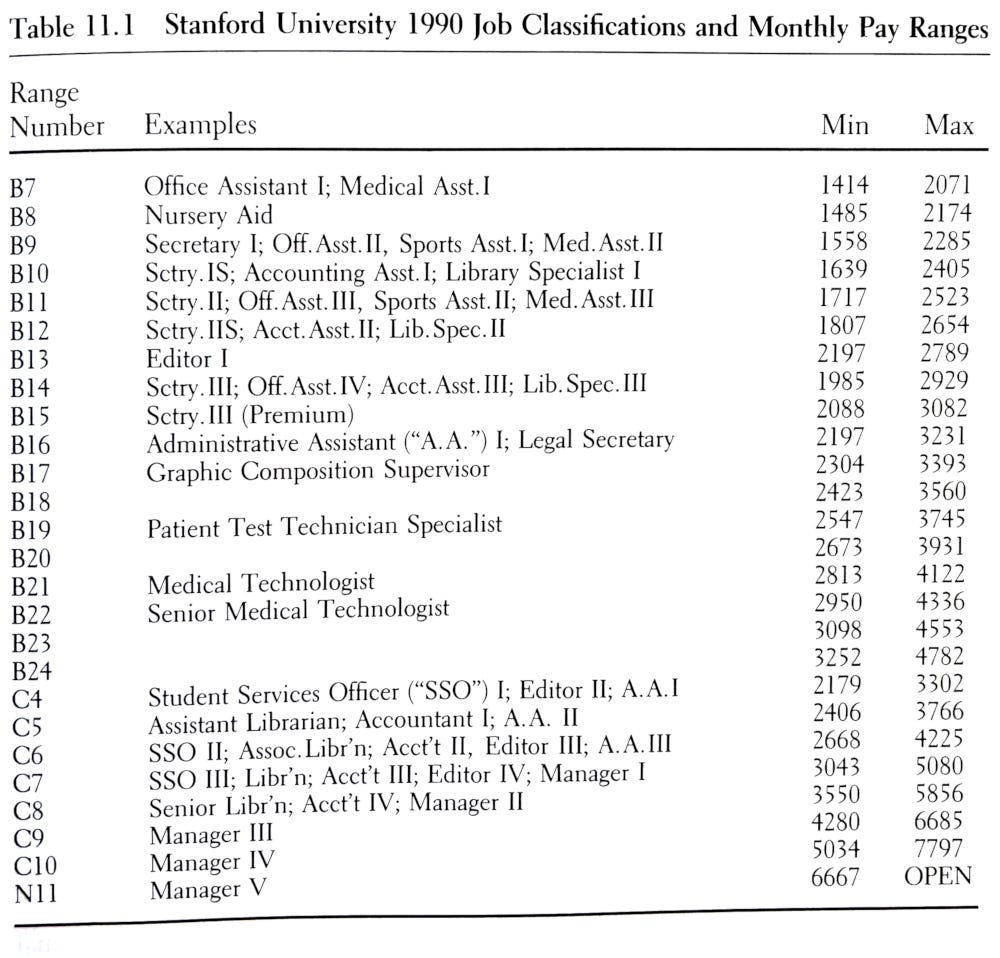

In the modern era, salary tables are a standard component of large organizations. With workforces numbering in the hundreds or thousands, enterprises require transparent and equitable pay structures. For example, the MBA textbook "Economics, Organization, and Management" presents a salary table used by Stanford University for its employees, showing job levels and associated pay ranges. Like the Mitsui system, this model creates a clear path for advancement and links effort with predictable rewards.

In both historical and contemporary examples, standardized compensation systems provide strong, scalable incentives. They show a clear contrast between the uncertainty of subsistence labor and a reliable framework that encourages long-term effort and productivity. This transformation—from unpredictable rewards in agrarian economies to structured incentives in modern enterprises—is a key mechanism by which large organizations drive economic development.

c) Enterprise as productivity booster

Large enterprises act as powerful engines for boosting productivity. There are two main reasons for this. First, a large enterprise functions as an internal labor market. The larger the organization, the larger the market for workers within it. This internal structure allows employees to specialize in narrower tasks and focus on areas where they hold a comparative advantage. As workers repeat specialized tasks, they gain experience and efficiency, ultimately raising overall productivity.

Second, enterprises enhance productivity by leveraging economies of scale. In small businesses, the resources available to invest in worker productivity are limited. Employers may not be able to afford advanced equipment, formal training programs, or professional human resources systems. Compensation structures may exist, but they are often informal or inconsistently applied due to the lack of dedicated personnel.

In contrast, large enterprises can overcome these limitations. They typically have sufficient capital to invest in expensive tools and technologies that improve efficiency. They also employ specialists dedicated to workforce training and maintaining structured compensation systems. These coordinated efforts create an environment in which employees are not only more capable but also more motivated to improve. The scale of the organization further reduces the per-worker cost of these investments, making it easier to sustain productivity growth across the entire enterprise.

In this way, large enterprises don't just benefit from productive workers—they actively cultivate productivity through specialization, structure, and scale. This dynamic is a key mechanism by which market expansion and enterprise growth contribute to economic development.

5. Statistical Evidence

The impact of market size on economic development is conceptually intuitive but empirically challenging to demonstrate. This is primarily because historical data on actual market size is scarce. Also, market size itself is heavily shaped by transportation efficiency—something difficult to quantify retrospectively. We know, for instance, that water transport was historically far more efficient than land transport, but we can't precisely measure how much this expanded a given country's market size at a particular time.