Technology in Economic Development: Innovation vs. Utilization

Modern discussions of technology and economic progress often center on innovation. Yet, technology only transforms societies when it is used. The broader the adoption, the greater its impact.

Summary

Technological progress matters most when innovations are widely used—not just when they are invented.

Historical examples, like Zheng He’s expeditions, show that even the most advanced technologies have limited impact if not deployed.

The Industrial Revolution spread through countries that actively learned and applied foreign technologies.

Enterprises—not individuals—drive large-scale adoption. Countries with fewer enterprises struggle to benefit from new technologies.

Utilization includes not only producing with new technology but also purchasing, consuming, and integrating it into daily life. These actions increase both productivity and well-being. However, this critical stage of technology’s impact is often missing from conversations about economic growth.

The Myth of Innovation Without Utilization

Innovators like James Watt and Steve Jobs rightly receive praise for reshaping modern life. But a new invention alone doesn’t change the world. The transformation comes when technology spreads, becomes affordable, and is embedded in daily life. This is where developing nations often fall behind—not because they lack access to ideas, but because they struggle to apply them.

A thought experiment helps illustrate this. Imagine all patents were made free and open to countries in the Global South. Would advanced pharmaceuticals or IT systems suddenly flourish across these regions? Likely not. Without skilled labor, capital, infrastructure, and especially enterprise-scale organizations to adopt and utilize these technologies, the benefits of innovation remain out of reach.

Lessons from History: Zheng He’s Missed Opportunity

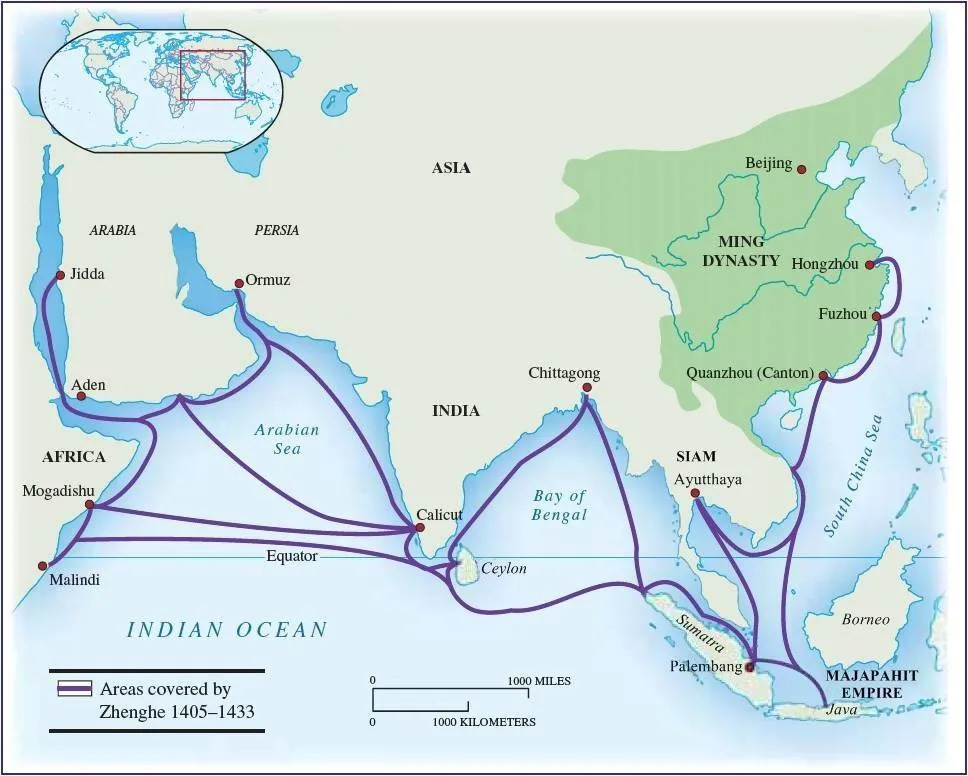

Between 1405 and 1430, China’s Admiral Zheng He led seven massive maritime expeditions using advanced ships and navigational tools. His fleet dwarfed that of later European explorers:

Ship Size: Zheng He’s ships likely ranged from 70–127 meters, far larger than Columbus’ Santa Maria (19 meters) or even Admiral Nelson’s HMS Victory (69 meters).

Fleet Size: 300 ships and 28,000 crew, versus Columbus’ 3 ships and 90 men.

Despite their technological edge, China halted the missions. Trade and exploration were eventually banned. Europe, by contrast, continued exploring and trading—applying inferior but widely used maritime technologies. The result: European powers, not China, came to dominate global oceans and trade.

The Industrial Revolution: Learning as a Competitive Advantage

The Industrial Revolution was not only about invention but also about learning. Nations that prospered—Britain, France, Japan, Sweden—actively studied and adapted foreign technology:

Officials, engineers, and merchants undertook learning tours abroad.

Travel diaries captured foreign techniques, which were then applied at home.

Publications like Lexicon Technicum (1704), Cyclopaedia (1802–1819), and Encyclopédie helped spread technological know-how.

These mechanisms allowed technologies to move from isolated inventions to societal tools.

The Enterprise Gap in Developing Countries

One of the central insights of Exchangism is the role of enterprises in shaping the modern economy. It argues that the rise and spread of enterprises were key to determining which countries became rich and which remained poor. Enterprises enabled the large-scale adoption and diffusion of technology, allowing societies to transform innovation into real economic productivity and social change. Enterprises make large-scale utilization possible:

They use in high-tech machinery to improve productivity.

They buy and license patents to stay competitive.

They develop, distribute, and maintain products using cutting-edge technologies.

In contrast, in many developing countries, a large share of the workforce operates in the informal sector. Without enterprises, there are fewer channels to spread and use technology—even if it is available.

Conclusion

History, current global patterns, and basic logic all point to the same conclusion: innovation is necessary, but insufficient. For technology to improve lives, it must be broadly and effectively used. That requires infrastructure, institutions, education, and especially enterprises to drive widespread adoption. Only then can innovation deliver on its full promise.