Why Bigger Markets Create Growth: Revisiting and Expanding Smith’s Economic Model [Exchangism Short Version]

How Market Expansion and Organizational Scale Drive Specialization, Innovation, and Investment

This post is a shorter, intro-style version of an essay on Exchangism. If you want the full story, click here.

Table of Contents

1. Smithian Economic Development Model: The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Extent of the Market

Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations (1776), identified a key principle of economic development: the extent of the market determines the degree of specialization. Using the example of a pin factory, he showed how dividing production into discrete steps—drawing wire, shaping the head, attaching it, and packaging—led to dramatically higher output. A single worker might make a few dozen pins a day, but with specialization, the factory could produce thousands.

Smith attributed this productivity gain to three mechanisms:

Skill improvement through repetition;

Reduced transition costs between tasks;

Innovation, as focused workers refine or automate their roles.

However, specialization depends on scale. In small or remote markets, demand is too limited to support specialized roles. In Scotland’s Highlands, for instance, a craftsman often had to be both carpenter and blacksmith. As Smith noted, "It is impossible there should be such a trade as even that of a nailer" in such isolated areas.

This observation underpins what we call the Smithian model of development: larger markets support deeper specialization, boosting productivity and driving economic growth.

2. Factors That Determine Market Size

The size of a market—shaped largely by geography—directly influences the degree of specialization and productivity within an economy. This helps explain why some countries developed faster and became wealthier than others. Understanding the key factors behind market size is essential to grasp the roots of economic growth.

a. Population Density

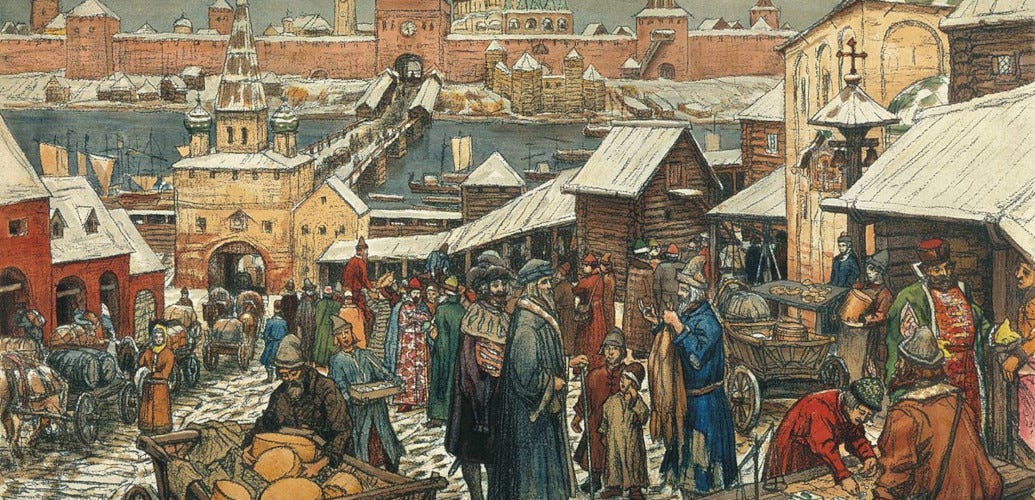

One of the most fundamental factors that determines the extent of a market is population density. Simply put, when people live closer together, the cost and difficulty of exchanging goods and services is dramatically reduced. Ancient cities—from Mesopotamia to Mesoamerica—emerged where people clustered, supporting specialization and trade. In modern history, economically advanced regions like East Asia and Western Europe reflected the same dynamic: high density enabled exchange, productivity, and growth.

b. Transportation

Efficient transport expands market reach and lowers costs. Historically, waterways—rivers and coastlines—were most effective. Civilizations near the Mediterranean, the Rhine, and Japan’s coasts benefited from maritime trade. Longer, irregular coastlines (Europe, Japan) created more ports and provided broader access to maritime transport than shorter ones (China, India), enabling earlier market integration and economic development.

c. Size of Business Organization

Large enterprises play a critical role in expanding market size. Their ability to move goods over long distances at lower costs—through in-house logistics or partnerships— allows broader trade and wider market access.

Beyond transport, large firms can mobilize capital to buy and sell goods in greater volume. For producers, this means access to larger, more consistent markets. For example, a traditional egg farmer might once have sold locally, but today, bulk buyers like food distributors enable industrial-scale production, making national and even global distribution feasible.

The transformative impact of large organizations became most visible with the emergence of joint-stock companies in the Netherlands and Britain. These entities coordinated vast trade networks and moved unprecedented volumes of goods, effectively creating the first truly global markets. Their scale redefined the boundaries of economic exchange—and marked a turning point in the rise of the modern economy.

d. Jungle

Tropical jungles obstruct mobility and trade, fragmenting markets. Southeast Asia, despite dense populations and long coastlines, developed slower than East Asia partly due to limited overland connectivity. Natural barriers, by restricting exchange, limit market size and slow economic progress.

3. Effects of a Bigger Market

a. Higher ROI and More Investment

A larger market typically increases return on investment (ROI), encouraging more investment in capital, knowledge, and infrastructure. Whether firms pursue an investment depends on whether expected gains exceed costs.

Consider a firm with $100M in annual revenue and $90M in costs. It considers buying a $200M machine that cuts costs by 10%. With 20-year depreciation, that’s $10M cost per year. A 10% cost reduction saves only $9M annually—less than the machine’s annual cost. The investment is not viable.

Now assume the firm expands to $130M in revenue and $117M in costs, assuming sales and cost increased proportionally . A 10% cut now saves $11.7M, which is more than $10M of annual cost—making the investment profitable. The same project becomes feasible because of market growth.

This is a key tenet of Exchangism: market expansion enables more investments to cross the profitability threshold, unlocking new capital deployment that was previously unjustifiable.

b. More Innovation

R&D is investment, and like any investment, its feasibility depends on expected returns—heavily influenced by market size.

Imagine an R&D project costing $3M that increases sales by 1% for five years. For a company with $100M in annual revenue, that’s $5M in added sales—worth the investment. For a firm with $50M in revenue, it yields only $2.5M—not worth pursuing. Larger firms in larger markets are more likely to innovate because their scale increases the potential payoff.

This pattern is consistent throughout history. In 19th-century England, growing textile exports to India transformed Manchester into a manufacturing hub. To meet rising demand, firms innovated rapidly. Transport needs between Liverpool and Manchester led to the first commercial railway—a catalyst for the Industrial Revolution.

It is true that small firms and even individuals innovate, exemplified by James Watt’s steam engine or today’s Silicon Valley startups. Yet even these innovators are driven by the expected returns—whether in the form of higher sales or large capital gains from an IPO. In a small economy, those returns are inherently limited. Moreover, many transformative innovations emerge not at the inception of a company but after it has scaled. Microsoft’s launch of Windows 95, the first internet-ready GUI operating system, came when the firm already had $6 billion in sales and nearly 18,000 employees. Apple introduced the Macintosh in 1983 with 5,000 employees and later the iPhone in 2007 with over 21,000. Scale provided not only resources but also the distribution capacity to turn breakthrough ideas into world-changing innovations.

Today, the most innovative firms—Amazon, Alphabet, Apple—operate globally. Their scale allows them to invest billions in R&D, apply innovations efficiently, and distribute them widely. They lead not because of one invention but because of the virtuous loop of scale, investment, and innovation.

c. Specialization of Enterprises into Comparative Advantage

The classical concept of comparative advantage—the idea that individuals or countries should focus on what they do best—also applies to firms. As markets grow, companies can specialize along their natural strengths.

In small markets, firms must do everything. A trading company might also operate retail stores. But in larger markets, scale allows each to focus: the wholesaler on logistics and procurement; the retailer on customer engagement. The result: higher efficiency across the entire value chain.

This dynamic is evident in global supply networks. A tech firm may focus on R&D and branding while outsourcing manufacturing to firms with lower costs or better equipment. Each participant specializes in its comparative strength, producing a more innovative and competitive final product.

In sum, market expansion enables specialization not only at the individual level but across entire firms. As organizations focus on what they do best, economies realize greater productivity, better products, and faster growth.

d. Bigger Markets Create More Enterprises, Strengthening Institutions

A larger market does more than generate profits—it creates more enterprises. And enterprises, in turn, strengthen the institutions that underpin advanced societies. (It also fosters urbanization and creates clusters of specialized people in society. Read more in The Network is Intelligence. How Urbanization, Connectivity, and Clusters Shaped Human Advancement.)

Agrarian societies illustrate the contrast. Peasants’ productivity was largely determined by the quality of their land and the climate. With little incentive or capacity to reshape legal or governmental frameworks, institutional development remained slow.

Merchants, however, faced a different reality. To operate across wider markets, they needed rules, contracts, and enforcement. Guilds sought recognition from rulers, but merchants also pushed for freedom to trade. They demanded courts to resolve disputes, clear property rights to protect investments, and regulatory systems that enabled rather than hindered commerce.

The building of canals in early modern Europe and Japan is a telling example. Such projects required coordination among merchants, landowners, construction workers, financiers, and state authorities. The pressure of commerce forced governments and societies to expand their institutional capacity.

As markets grew larger, so did the scale of enterprises—and with them, the political and social weight to demand stronger institutions. Over time, this dynamic transformed entire societies. Wealthy commercial economies developed not only advanced business institutions but also capable schools, armies, hospitals, and governments. These were not accidental by-products but the result of continuous negotiation and interaction among stakeholders in a complex society.

In this way, bigger markets do not just create more business—they foster the institutional ecosystems that sustain long-term economic and social development.

4. Counterexample: China and India

At this point, one might ask: if the size of the market is so critical, why did historically large and populous countries such as China and India not experience modern economic development? After all, both regions contained vast populations and ancient traditions of commerce.

The answer lies in the distinction between population size and effective market size. Before the 19th century—prior to the spread of railways and later automobiles—long-distance exchange relied primarily on water transport. Rivers, canals, and coastlines were the arteries of commerce, as moving goods over land was prohibitively costly.

While China and India did make extensive use of waterways—the Yangtze, Yellow, and Ganges rivers were major commercial corridors—large portions of their territory remained economically isolated. Inland regions far from navigable rivers or seaports could not easily participate in wider trade networks. As a result, despite their vast populations, much of their exchange occurred in fragmented, local markets.

This stands in stark contrast to Europe and Japan. Europe’s jagged coastlines, dense network of navigable rivers, and proximity of most settlements to water created a tightly interlinked commercial geography. Even small farmers were drawn into wider regional markets through riverine and maritime trade. Similarly, Japan’s island geography meant that nearly all regions were close to the coast, enabling relatively easy integration into a national market.

Another factor was institutional. In Europe, growing commercial integration strengthened the bargaining power of merchants and urban elites, who pressed governments for policies and institutions favorable to trade and innovation. In China and India, the predominance of the peasantry—constituting the bulk of the tax base—meant that political authorities had less incentive to restructure institutions in favor of commerce. The dynamism described earlier in section 3-d (“Bigger Markets Create More Enterprises, Strengthening Institutions”)—where geography fosters pressure for institutional change—was far weaker in these agrarian empires.

In short, China and India illustrate that a large population is not equivalent to a large market. Without the transport technologies necessary to integrate their vast territories, much of their economic potential remained locked in localized, self-sufficient economies. It was only with the arrival of modern infrastructure in the 19th century that these large populations could begin to translate into truly integrated markets.

Conclusion

Adam Smith’s core insight—that the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market—remains the foundation of economic growth. Larger markets enable deeper specialization, higher returns on investment, and faster innovation, setting in motion a self-reinforcing cycle of productivity and progress.

History shows this clearly. Europe and Japan, with dense populations and easy access to waterways, achieved early market integration and economic dynamism. By contrast, regions like inland China and India, despite their vast populations, were slowed by fragmentation and barriers to exchange. Market size, not just population, determined the pace of development.

Today’s global economy makes this principle more relevant than ever. Digital platforms, global supply chains, and multinational enterprises have expanded the effective market to a planetary scale, creating unprecedented opportunities. Economic growth is not an accident of history but the predictable outcome of expanding exchange. Bigger markets don’t just support growth—they generate it.